Edward Norton wanted to make a movie based on Jonathan Lethem's novel Motherless Brooklyn when it was first published in 1999. 20 years later, the story finally comes to the screen, with Norton as writer, producer, and star. He moved the setting from the '90s to post-WWII and changed some of the storyline. But the central figure remains the same, Lionel Essrog, a detective who struggles with—and relies on—what today would be diagnosed as Tourette Syndrome and OCD. In an interview with RogerEbert.com, Norton talked about the noir-ish score by Daniel Pemberton, the "treasure hunt" to find period locations in New York, and movies about "complexity of value."

This may be my favorite movie score of the year.

Meeting Daniel Pemberton was one of the strokes of luck of the whole thing. We literally almost didn't meet because he was working on "Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse," and he was working so late. I was in London and someone I trust was saying, "I really do think you should meet with him," and it was one of those things where it was 1:00 am, he was saying “I’ll be done in minutes, can you meet at a bar?” and finally I was like, “Sure, why not?” So I met him at like 1:30 in the morning at a bar in London and as soon as he walked in I had this feeling, "This guy is much more eccentric than I thought he was." I had an image of him as a sort of a stuffy British guy. I thought he was going to come in a tie.

I mentioned to him that I really liked the score "Chariots of Fire" by Vangelis, specifically because of its simple classical piano under this synth thing and that I wanted to do a kind of a neo-noir fusion score. I thought to myself that "Chariots of Fire" can be very polarizing; like some contemporary guys will look at you like, "Oh, you didn't just cite Vangelis, did you?" but he literally went, “I cannot believe you just mentioned that. The first 25 thousand quid I ever made I bought the CSAT, the same keyboard as Vangelis made that score on,” and he literally said something like, “You had me at Vangelis.”

I said to him, "I want like half Miles Davis half Radiohead. I want a big, lyrical, thematic jazz score but I also want this element of dissonance because of the character’s brain." He just did wonderful, wonderful stuff. It's hard to even really articulate how impossible what he did is, because he wrote a huge score, a very complex score in less than four weeks and then turned around and produced it in less than two weeks. It’s inconceivable to me that he got this done in the time that he got it done.

Quincy Jones walked out of the movie the other night and he said, “You were great, but I can't get my head around the music in that film.” Wynton Marsalis was only originally going to play the stuff that’s played by the band in the film. He was going to be the horn under my actor. I asked him to do one or two key moments of lead horn on some of those particular themes, Lionel’s theme and Rose's theme, and he read the score sheets and he said, “This is just great; you have to let us play over all of it.” And so he and his guys played all the core stuff. I don't think anybody's written a better score than this in the last 10 years; I think it’s as good a film score as has been written in quite a while.

The music becomes very important in the film. The word that I remember the most from the book was "imperative." Lionel feels this imperative compulsion that he has to fight against all the time. But we see in the film that for him the music is the opposite of an imperative; he connects to jazz in a very organic way and it feels freeing.

In the book there's a great passage about his love of Prince’s music, and I wanted to transpose that to make sure there was that same idea of how music can have volatility in jazz and bop in particular. If there's any music that's has a tourettic quality to it, I would say it’s bop; the propulsive kind of staccato looping.

And also, honestly I like just those things that stick in your head. In Jack Kerouac’s book On the Road there's that one great passage about Dean Moriarty by the stage whooping and yelling and scatting like a white beatnik whooping and scatting with the jazz players, and it is sort of ridiculous but endearing. I thought that seems like Lionel. The great thing about jazz and the idea of a person with Tourette’s getting caught up in jazz is, it can become non-verbal and it can become you having the experience with him. You've been with him long enough inside his condition that you can share in the feeling of, “Oh, it feels so good to see him relating.”

You decided to change the setting to 40 years earlier than the era of the book.

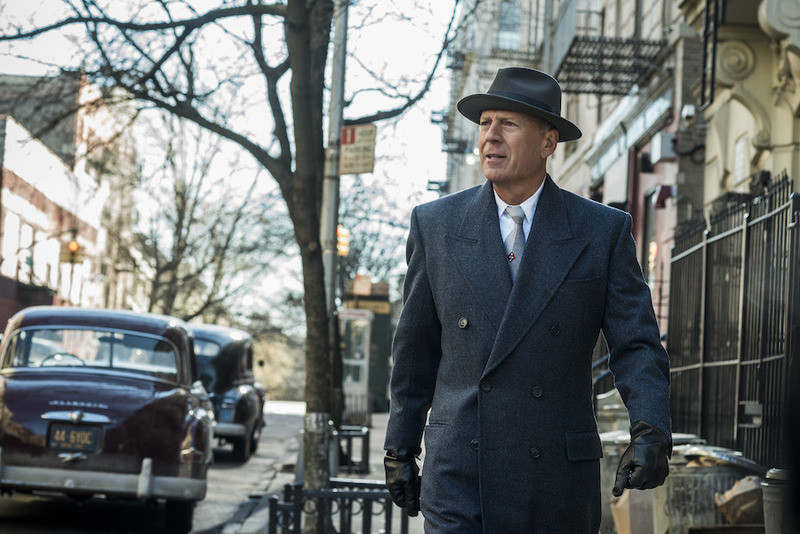

The book is set in 1999 and we made this big decision to take the essence of the character’s isolation, his relationship with his boss, with the guys around him, and to transpose it back into the '50s because in the novel they feel like men living in this pocket of Brooklyn that hasn't moved in time. There’s an almost surreal kind of meta quality. They’re like hard-boiled gumshoes in the modern world. But film is very literal, and I said to Jonathan that I was worried about it feeling tongue-in-cheek. I'm not a big fan of what I call air quotes in film. I like "LA Confidential" and "Chinatown" and "The Big Sleep" and any film that in looking at the period just takes it very seriously, plays it very straight. I felt that it would diminish the emotional potential in Lionel's isolation if you put it in the modern world.

But that creates a real headache for you as a director and producer, re-creating the era.

We did like a treasure hunt in the city for the places where with minimal manipulation you are right in there. New York City's an incredible three-dimensional maze of old and new. We were like, "Wow, here we’ve got six blocks that we can run cars up in a car chase and other than signage there's nothing wrong with it; the buildings are all right and it leads to the bridge and bridge goes to Queens and the bridge is as it was.” You end up having to create a patchwork quilt to shoot around. "Well, here was the real Triboro Authority building built in the '30s; it looks perfect, but the inside is all chopped up and modernized, so what are we going to do?" So there's the room that we make inside for his office and imagine the imperial view of the bridge and river that you would think he should have and the pool and where he kicks everybody out to swim alone. You find that’s a real public pool in Harlem but the exterior is all trash so you shoot that somewhere else. [Production designer] Beth Mickle is incredibly audacious in her capacity to say, "I know how to do that.” People like that end up being your heroes.

Was there a particular period detail that was essential for you, or one that was particularly hard to get right?

Cars are a nightmare. And by that I mean if you're going to throw a bunch of them around in a car chase, the problem is that none of them work, and so you have to have three or four identicals of anything that you need to work in a given moment because they will break down and that's tricky.

Probably the two things that were rough or bold on the budget we had were doing a big Hitchcock-style fight on a fire escape, and knowing that you have to build that whole exterior wall of an apartment building, you have to put a fire escape on it; so you put cranes there and you have to have green screen all around it and you have to end up making it look real and good. The old Penn Station -- lot of people at a certain point were looking at me like, "Can't this scene happen in a bus station?" No. There are certain things that are emblematic of what you lose, as Paul says, “if you're not looking out, if people aren’t looking out for these things if they walk around like Hindu cows thinking we live in a democracy, nothing can go wrong," you lose Penn Station. You lose entire neighborhoods and stable communities because no one's looking out for them and no one is standing up. You also lose literally the gateway to your city. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan used to quote architect Vincent Scully: "One entered the city like a god. One scuttles in now like a rat." You lose an exalted sense of the entrance and exit of the biggest city in the country and you can’t get that back. You look at the way the French just reacted to the Notre Dame burning. Those are our Notre Dames. We had that and we tore it down for a shady stadium, for a concert hall, an arena that isn’t even a good one.

But you didn't put it in good vs. evil terms. There are millions of movies with the developer as the bad guy; you didn't do that here.

One of the films that set my aspirational bar when I was of a certain age was "Do The Right Thing." It was incredibly original filmmaking. It was so dynamic. It also was so incredibly sophisticated for this very young filmmaker at the time. It was like it took on things that nobody talked about, let alone in a film, and it didn't answer the question. It clearly set up this whole dialogue and then at the end it put up a quote from Martin Luther King that said like, essentially violence is not a response that will create a progress, and then Malcolm X saying sometimes violence is the only rational answer, and then picture of the two of them together and fade out. Basically it was like, "Oh my God, he just literally said over to you." He just said, "I’m going to tell you a story, now you assess it." I think when you have those things that make you realize, "I have to go to the box office right now and buy a ticket and go back in and watch this again to figure out what the hell," that's like activated filmmaking to me. That's like a film is seeking an activated audience, as opposed to giving them a Xanax.

I think that's the just the most fantastic thing. If I didn't think you could do that I would do something else. I remember when we made "The 25th Hour," Phil Hoffman and I were talking about how Spike was it for a lot of us, and he still is. There are still not many people who are as committed as he’s been over the last 30 years to saying the hard things about living in this country, and what the hell are we doing about them, how are we talking about them? We don't have that many committed social moralists saying, "We've got to talk about this. We've got to deal with it. We've got to think about it." As iconoclastic as Spike seems as a person, you realize his filmmaking is enormously mature and full of compassion. He has compassion for Danny Aiello the racist pizza maker; he has a lot of understanding and compassion that he gives them voice.

That idea of complexity of value -- that there are difficult questions and we need to talk about them -- to me that's a pretty high bar.

The most extreme is movies that tell us a cinematic universe of heroes is going to come and save you. Just eat your popcorn. Your assistance not required. I think much, much more activating and much more authentically inspiring is anything in which you see yourself reflected in someone else, having to fight through struggles that you can relate to. It is incredibly tempting to sink into your own daily misery and just be like, "I can't take that on," but I think anything that gives people the portrait of someone finding the bandwidth for caring, anything with a certain provocation in it, that is pretty healthy.

Nell Minow is the Contributing Editor at RogerEbert.com.