Although histories of the American cinema, especially those of the young filmmakers who arrived in the Seventies and went on to dominate the industry, often lump Brian De Palma with such influential contemporaries as Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, the truth of the matter is that De Palma was never quite their equal, either critically or commercially. Looking back, it isn't too difficult to see why this was the case. Throughout his entire career, De Palma has pursued a vision that is dark, cynical, overtly violent and sexual, and deeply mistrustful of most forms of higher authority. His vision was designed to shake viewers out of their complacency and make them feel something—fear, anger, paranoia and the like—that would stick with them long after the rolling of the end credits. Alas, these are not necessarily things that the mass audience necessarily wants to experience on a Saturday night out at the movies. As a result, the films of his aforementioned contemporaries (which were no less personal in nature—it was just that their personal tastes jived more consistently with that of the public) received the kind of critical raves and/or zillions in ticket sales that De Palma could only dream of, though he did get the consolation prizes of a loyal cult following in his home country, and even greater admiration from critics and moviegoers in Europe.

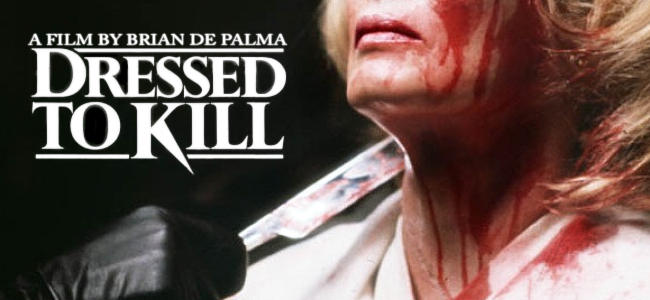

De Palma did have his share of hits from time to time. "Carrie" was a horror smash that was not only popular with critics and audiences, but which also earned Oscar nominations for co-stars Sissy Spacek and Piper Laurie. De Palma's controversial 1983 remake of "Scarface," although not a hit at first, would eventually go on to become an enormous hit on home video and would earn a place of prominence as a key influence on hip-hop culture. In addition, his adaptations of the boob tube favorites "The Untouchables" and "Mission: Impossible" were the kind of blockbusters that put him, however briefly, into the same orbit as Spielberg, Lucas, et al. However, in these cases, De Palma was able to find properties conceived by other people that would allow him to explore his obsessions within frameworks with a more overt commercial appeal. In fact, it could be argued that there was only one point in time when De Palma's singular vision, pure and unfettered, found true favor in America, both critically and commercially, and that came with the release of his 13th feature film, the knockout suspense thriller "Dressed to Kill." An audacious blend of black humor, blood-red violence and pure cinematic skill, the film was a hugely controversial success when it was released in the summer of 1980 and, as a look at the new Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection confirms, the passage of time has not caused it to lose its ability to arouse, amuse, enrage and terrify viewers in even the slightest.

If nothing else, "Dressed to Kill" doesn't waste any time before getting down to the business of getting audiences all hot and bothered. In the very first sequence, the first of many to highlight Ralf Bode's exquisite, dream-like cinematography, upper-class New York housewife Kate Miller (Angie Dickinson) is in the shower fantasizing while watching her husband shaving himself with a straight razor on the other side of the curtain. The scene has the dreamy, languorous feel of a softcore photo shoot come to life (a sense accentuated by the fact that Victoria Johnson, the model serving as Dickinson's body double, had previously posed for "Penthouse"). But this is a shower scene, after all, and between the obvious connotations with the most famous scene from "Psycho" (which must have resonated even stronger than expected when first released since Alfred Hitchcock had passed away only a couple of months before, with its ads proclaiming De Palma as "The Modern Master Of Suspense") and the shower scenes that De Palma himself had previously staged for effects both comedic ("Phantom of the Paradise") and horrific ("Carrie") in tone, many viewers must have looked upon it with at least some degree of unease. Right on cue, the mood shifts from the erotic to the frightening as a barely-seen man comes up from behind and attacks her, grabbing her by the throat so that she cannot scream.

The whole thing is, of course, a dream—something cooked up by Kate in her mind to help distract her from the grim approximation of lovemaking that she is enduring with her clueless husband. (The news report on the radio playing in the room generates more erotic heat than he does.) As we soon discover, Kate's sense of alienation is not solely limited to her husband. She has a brainiac son, Peter (Keith Gordon), whom she clearly loves but whose obsession with building computers and other gadgets is something that she can barely understand on even the most basic of levels. She sees a psychiatrist, the eminent Dr. Robert Elliott (Michael Caine), and he is crisp and professional to a fault. He is so professional, in fact, that when Kate flat-out propositions him, he turns her down without a single hesitation—he is her doctor and, more importantly, he has a wife and is unwilling to risk his marriage. By the time Kate leaves his office, she is even more frustrated than she was when she went in, and just one look at her shows that she is someone who is truly starving for affection and will now take it wherever she can find it.

This leads Kate to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (played here by the Philadelphia Museum of Art), and the film to what is arguably its high cinematic point. For nearly nine dialogue-free minutes (De Palma had written a voiceover for Dickinson but abandoned it as unnecessary), Kate wanders through the halls and eventually catches the eye of what appears to be the mystery man of her fantasies. She alternately pursues and is pursued by the stranger (while the Steadicam, then still in the early days of its use as a cinematic tool, glides right along with them) until the two finally come together, first in the back of a taxicab and later at his apartment. This bit of carnal fulfillment would seem to be the stuff of Kate's dreams but it quickly devolves into a nightmare with the discovery of something in the now-dozing man's apartment that sends her fleeing until she realizes that she has left something important behind. She gets back into the elevator to retrieve it but when the door opens next, a mysterious blonde wielding a straight razor appears out of nowhere to slash Kate to death in a grotesque fulfillment of the darker side of her masochistic fantasies.

Meanwhile, on another floor, Liz Blake (Nancy Allen), a high-priced and investment-minded call girl, is wrapping up business with a client when the elevator door opens revealing Kate's mutilated body. She instinctively reaches out to help—the john has naturally disappeared—but all she winds up with is a brief glimpse of the killer in one of the elevator's mirrors and the murder weapon in her hand. Inevitably, this means that the cop assigned to the case, Marino (Dennis Franz at his sleaziest) doesn't believe her story about the blonde and considers Liz to be the prime suspect in Kate's murder despite the lack of any plausible motive. The blonde is out there, of course, and this leads to the sequence that would have been uniformly considered the highpoint of the film if it weren't for the unquestioned masterpiece that was the museum set-piece. Out on the streets after a job one night, Liz finds herself being pursued by the blonde and tries to evade her by getting on the subway, a move that only puts her in more danger when she runs across a group of young black men, and they start chasing her as well with rape on their minds.

The sequence is quintessential De Palma from start to finish. From a formal perspective, it is a thing of beauty—entire classes could be taught on the way that he brings together all of the techniques of filmmaking into the kind of sustained burst of pure cinema that you want to watch again as soon as it ends, just to wallow in its pleasures a second time. While all of this is going on, De Palma is also ratcheting up the suspense to heart-stopping levels by crafting the sequence in such a way that makes us acutely aware of just how isolated a person can be in a seemingly public place, and of just how many places there are in a seemingly limited locals from which a figure of menace can suddenly appear. Finally, and this what makes it so distinctively De Palma, the scene is just as funny as it is frightening. In just a few short minutes, De Palma takes all of the fears that one might have about being out late at night, especially in New York circa 1980—that everyone is out to attack you and there is never a cop in sight when you need one—and amplifies them to darkly satirical extremes. Of course, the racial aspect inherent in the scene is potentially troubling but even here, De Palma is slyly using the outrageousness of the entire situation (the only African-American characters of any consequence in the film are a bunch of guys driven to potential rape merely at the sight of a white woman) as a way of distracting viewers from the other potential danger involved—that pesky murderous blonde—until just the right moment.

Liz survives, thanks to the unexpected assistance of Peter, who, feeling guilty over his mother's death, has been doing some snooping around on his own. Together, the two figure out that the killer must be one of Elliott's patients. But when Liz lets Marino in on their suspicions, he says that without any tangible proof, he can't get a court order to examine his files, since Elliott will not voluntarily turn them over because of doctor-patient privilege. However, Elliott is also convinced that one of his patients—a would-be transsexual named Bobbie whose sex-change surgery he refused to approve—is indeed the killer and is trying to track him down, especially since it appears Bobbie stole his razor from his office in order to use it on Kate. To get the needed evidence and save her own skin, Liz hits upon a plan to go to Elliott's office one night, and use her considerable powers of seduction to distract him long enough to get the needed evidence from his datebook while Peter keeps an eye on things from the outside. To put it simply, things do not go as expected, but just when you think it is all over and you can relax, the film still has a couple of nasty surprises left to deploy. You didn't think the guy responsible for the sucker punch at the end of "Carrie" was going to let viewers off that easy, did you?

Watching "Dressed to Kill" today, it is a little jolting to discover just how much of its power to shock, amuse and amaze viewers it has managed to retain over the last 35 years. This is one of those films where everything works so well throughout that it all but requires at least two viewings—the first in order to become completely absorbed in the story, and the second to allow viewers to see and recognize the extraordinary craft that went into bringing it to the screen. This is easily one of the most immaculately crafted films of De Palma's entire career and not just in simple stylistic terms. The screenwriting—the area that has always been De Palma's weakness in the eyes of many—is a beauty. Its story expertly toys with audience assumptions (such as the feeling that the entire film is little more than a riff on "Psycho") before sending them in unexpected directions. The dialogue has a snap to it that gives life to even the most exposition-heavy exchanges (the scenes between Liz and Marino, two equally foul-mouthed masters of their trades who think they have each others number, are absolutely inspired) and the stylistic flourishes, such as De Palma's use of split-screen imagery, never feel like distractions. (In one of the most impressive examples, we see two characters watching an episode of Phil Donahue's talk show involving transsexuals—the very episode that proved to be a crucial inspiration in the development of the film—with very different degrees of interest that proves to be most revealing.) The performances are excellent across the board—De Palma rarely gets credit for his work with actors but the performances here are some of the liveliest in any of his films. And yeah, let it be said that when it comes to building and finally releasing tension and suspense in purely cinematic terms, few have ever come close to approaching to the effects that De Palma pulls off here with an almost diabolical sense of glee.

That said, there are two points of contention that people have had with "Dressed to Kill" over the years and they should be addressed here. The first is the complaint many have had that a lot of the key story points do not make any logical sense when one thinks about them for more than a second or two. It is true that if you sit down and carefully lay out the story points, they do not always add up. For starters, how could the killer have possibly known that Kate would have forgotten something in the apartment that would have required her return? The easy answer would be to point out that the narratives of Alfred Hitchcock were not exactly the most airtight creations either (if you ever want to drive yourself mad some night, try getting all of the elements of "North by Northwest" to add up sometime) and that De Palma relates the story with such style that the logical gaps do not manifest themselves until long after the movie is over. However, I am more and more convinced that we are supposed to look upon the story as maintaining a sort of dream logic throughout that allows things that would otherwise come across as too implausible to be believed to somehow make a certain degree of success.

Yes, I am fully aware that explaining the seemingly inexplicable elements as being all a dream is usually the last refuge of a desperate essayist. But in this case, I think it does make sense once you begin to realize that De Palma has faked us out once again. Having been compared, usually unfavorably, to Alfred Hitchcock throughout his career—even though he didn't so much copy Hitchcock's work as he did use it as a jumping-off point for his own unique cinematic obsessions—he must have realized that any suspense story he told would lead to similar comparisons, and used that knowledge to confound expectations. Although the bare bones of "Dressed to Kill's" story did indeed owe something to "Psycho," the filmmaker that seemed to be De Palma's central inspiration this time around was the equally legendary Luis Buñuel, a man whose works so closely blended together reality and fantasy that it was often impossible to be certain as to which elements of his stories were straightforward and which ones crossed the line into surreal fantasy. In hindsight, this should have been obvious right from the very first scene—while people noted the use of a shower and immediately assumed "Psycho," they failed to notice that opening a story with a cool blonde enacting what turns out to be a sadomasochistic sexual fantasy is exactly what Buñuel did in his 1967 masterpiece "Belle du Jour." If one looks at the film as a Buñuelian homage, its more overtly bizarre moments begin to take on the former of an extended bad dream from which the characters cannot easily emerge unscathed. In fact, the final image of the film is of the its most likable character waken up from a grisly nightmare—based on everything we have seen, it is perfectly plausible that the entire story that we have just seen has been part of that dream up to that point and for all we know, the awareness that it is just a dream may be just another level of the dream. (Sure, you may reject this as an explanation, but I am willing to bet that you would be a lot more open to this interpretation if it was a David Lynch joint under discussion.)

The second, and potentially more troubling aspect of "Dressed to Kill," is the notion that the entire film is nothing more than an exercise in wild misogyny. More specifically, that De Palma gets to punish a woman for exhibiting erotic desire by brutally murdering her in an especially unpleasant and sadistic manner, to somehow make her pay for her transgressions against acceptable female behavior. There are plenty of thrillers that could, and should, get criticized alongs those lines, but not this one. Unlike a lot of the mad slasher films of the time that "Dressed to Kill" did get lumped in with—films in which women were often looked upon as interchangeable figures who existed only to strip off their clothes and get slaughtered—De Palma genuinely likes and sympathizes with his female characters. One of the reasons that the opening scenes are so effective is that he puts us so firmly on Kate's emotional wavelength, so that we completely feel for her at every step of the game. We share in her frustrations, we revel in her long-awaited release and when she is murdered, we so fully identify with her that we are genuinely knocked for a loop in a way that we wouldn't have been if she had been presented in a more two-dimensional manner. Likewise, Liz may be that most tiresome caricature—the hooker with a heart of gold, not to mention the occasional IRA—but De Palma and Allen have invested her with enough kooky charm, cool intelligence and bravado to pull off the task of taking over the responsibilities of driving the story along following Kate's abrupt departure.

Compared to them, the film's depiction of men is far less favorable. Kate's husband and Marino are walking depictions of piggish behavior (with his leather jacket and tons of gold jewelry, Marino seems like he would be more at home committing sex crimes instead of investigating them) and though Elliott seems a model of decorum, the way he constantly looks at his reflection in the mirrored surfaces of his office while Kate unloads her problems suggests a certain degree of barely-masked self-absorption. The only male character who isn't presented as some form of boor or psychopath is Peter, and that can easily be explained by the fact that while he may be a genius, sexuality has not yet creeped into his horizon. When he winds up spending the night with Liz, there is not even the hint of the possibility of seduction—it seems more like a slumber party than anything else. As for Bobbie—well, Bobbie may yearn to be a woman, but as events spell out, the mindset is clearly still dominated by the remaining male mindset with destructive results for all involved.

As for the Blu-ray itself, it was originally scheduled to be released last month until a mistake in the framing of the transfer caused a delay so that Criterion could make new discs correcting the error. That mistake aside, the disc is definitely a keeper for anyone with even the slightest interest in the film or De Palma. All of the bonus features that were produced for its 2001 DVD iteration have been retained for this edition—an in-depth documentary on the making of the film from Laurent Bouzreau that includes interviews with most of the key participants, a gallery of De Palma's storyboards for the key sequences, a short interview with actor-turned-director Keith Gordon about working with De Palma, and a video essay illustrating the various and oftentimes silly ways in which the film was cut up in order to get the all-important "R" rating from the MPAA. (The version presented here is, of course, the uncut and full-strength version that De Palma initially conceived and which played theatrically in Europe.)

Criterion has also included a number of new bells and whistles as well, starting with a new 4K transfer that—framing issues aside—looks pretty nifty. Although De Palma has never been one for supplying commentary tracks for his films, he does sit down for an extensive interview with filmmaker Noah Baumbach, and while some of the material duplicates stuff found in the making-of documentary, it is still worth watching. The stunning work of cinematographer Ralf Bode is also celebrated in a featurette that includes commentary from director Michael Apted. Finally, there are a slew of new interviews with a number of the participants—Nancy Allen, producer George Litto, composer Pino Donaggio (who has worked with De Palma consistently over the years and who contributes one of his very best scores here), poster designer Stephen Sayadian and, most intriguingly, model Victoria Johnson, whose recollections of her time working as Angie Dickinson's body double in the infamous opening scene offers a revealing-—no pun intended-—look into the ways that films are really made.

A moderately insightful critic, full-on Swiftie and all-around bon vivant, Peter Sobczynski, in addition to his work at this site, is also a contributor to The Spool and can be heard weekly discussing new Blu-Ray releases on the Movie Madness podcast on the Now Playing network.