Now streaming on:

"Chicago" continues the reinvention of the musical that started with "Moulin Rouge." Although modern audiences don't like to see stories interrupted by songs, apparently they like songs interrupted by stories. The movie is a dazzling song and dance extravaganza, with just enough words to support the music and allow everyone to catch their breath between songs. You can watch it like you listen to an album, over and over; the same phenomenon explains why "Moulin Rouge" was a bigger hit on DVD than in theaters.

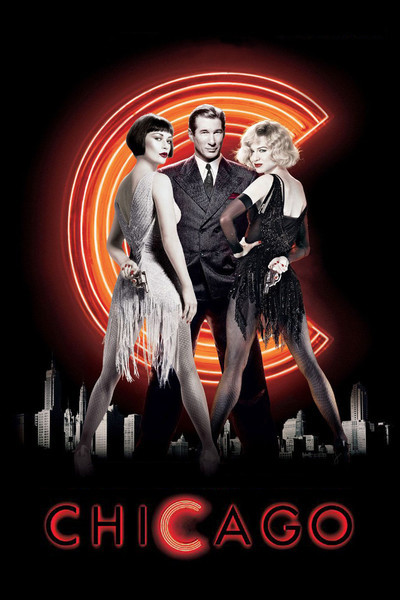

The movie stars sweet-faced Renee Zellweger as Roxie Hart, who kills her lover and convinces her husband to pay for her defense; and Catherine Zeta-Jones as Velma Kelly, who broke up her vaudeville sister act by murdering her husband and her sister while they were engaged in a sport not licensed for in-laws. Richard Gere is Billy Flynn, the slick, high-priced attorney who boasts he can beat any rap, for a $5,000 fee. "If Jesus Christ had lived in Chicago," he explains, "and if he'd had $5,000, and had come to me--things would have turned out differently." This story, lightweight but cheerfully lurid, fueled Bob Fosse, John Kander and Fred Ebb's original stage production of "Chicago," which opened in 1975 and has been playing somewhere or other ever after--since 1997 again on Broadway. Fosse, who grew up in Chicago in the 1930s and 1940s, lived in a city where the daily papers roared with the kinds of headlines the movie loves. Killers were romanticized or vilified, cops and lawyers and reporters lived in each other's pockets, and newspapers read like pulp fiction. There's an inspired scene of ventriloquism and puppetry at a press conference, with all of the characters dangling from strings. For Fosse, the Chicago of Roxie Hart supplied the perfect peg to hang his famous hat.

The movie doesn't update the musical so much as bring it to a high electric streamlined gloss. The director Rob Marshall, a stage veteran making his big screen debut, paces the film with gusto. It's not all breakneck production numbers, but it's never far from one. And the choreography doesn't copy Fosse's inimitable style, but it's not far from it, either; the movie sideswipes imitation on its way to homage.

The decision to use non-singers and non-dancers is always controversial in musicals, especially in these days when big stars are needed to headline expensive productions. Of Zellweger and Gere, it can be said that they are persuasive in their musical roles and well cast as their characters. Zeta-Jones was, in fact, a professional dancer in London before she decided to leave the chorus line and take her chances with acting, and her dancing in the movie is a reminder of the golden days; the film opens with her "All that Jazz" number, which plays like a promise "Chicago" will have to deliver on. And what a good idea to cast Queen Latifah in the role of Mama, the prison matron; she belts out "When You're Good to Mama" with the superb assurance of a performer who knows what good is and what Mama likes.

The story is inspired by the screaming headlines of the Front Page era and the decade after. We meet Roxie Hart, married early and unwisely, to Amos Hart (John C. Reilly), a credulous lunkhead. She has a lover named Fred Casely (Dominic West), who sweet-talks her with promises of stardom. When she finds out he's a two-timing liar, she guns him down, and gets a one-way ticket to Death Row, already inhabited by Velma and overseen by Mama.

Can she get off? Only Billy Flynn (Gere) can pull off a trick like that, although his price is high and he sings a song in praise of his strategy ("Give 'em the old razzle-dazzle"). Velma has already captured the attention of newspaper readers, but after the poor sap Amos pays Billy his fee, a process begins to transform Roxie into a misunderstood heroine. She herself shows a certain genius in the process, as when she dramatically reveals she is pregnant with Amos' child, a claim that works only if nobody in the courtroom can count to nine.

Instead of interrupting the drama with songs, Marshall and screenwriter Bill Condon stage the songs more or less within Roxie's imagination, where everything is a little more supercharged than life, and even lawyers can tap-dance. (To be sure, Gere's own tap dancing is on the level of performers in the Chicago Bar Association's annual revue). There are a few moments of straight pathos, including Amos Hart's pathetic disbelief that his Roxie could have cheated on him; he sings "Mr. Cellophane" about how people see right through him. But for the most part the film runs on solid-gold cynicism.

Reilly brings a kind of pathetic sincere naivete to the role--the same tone, indeed, he brings to a similar husband in "The Hours," where it is also needed. It's surprising to see the confidence in his singing and dancing, until you find out he was in musicals all through school. Zellweger is not a born hoofer, but then again Roxie Hart isn't supposed to be a star; the whole point is that she isn't, and what Zellweger invaluably contributes to the role is Roxie's dreamy infatuation with herself, and her quickly growing mastery of publicity. Velma is supposed to be a singing and dancing star, and Zeta-Jones delivers with glamor, high style and the delicious confidence the world forces on you when you are one of its most beautiful inhabitants. As for Queen Latifah, she's too young to remember Sophie Tucker, but not to channel her.

"Chicago" is a musical that might have seemed unfilmable, but that was because it was assumed it had to be transformed into more conventional terms. By filming it in its own spirit, by making it frankly a stagy song-and-dance revue, by kidding the stories instead of lingering over them, the movie is big, brassy fun.

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

113 minutes

Christine Baranski as Mary Sunshine

Renée Zellweger as Roxie Hart

John C. Reilly as Amos Hart

Lucy Liu as Kitty Baxter

Catherine Zeta-Jones as Velma Kelly

Richard Gere as Billy Flynn

Taye Diggs as Bandleader