“We’re Americans.”

That’s the identification offered by Red (Lupita Nyong’o) to her inquisitive and terrified doppelgänger Adelaide, the former appearing at the latter’s summer home with bulging eyes, a voice she has not used in decades, and a profound anger. As Red sits with her own family, which look like a bizarro version of Adelaide’s, she wields her weapon of severance—a pair of golden scissors—and clues viewers into the execution event at the center of Jordan Peele’s “Us.” As we learn about the purpose of The Untethering, and where Red truly came from, “Us” becomes an American nightmare about our divisive selves taking over.

That very line of dialogue could have been an alternate title for Peele’s sophomore film, but it speaks to something that’s very pertinent about “Us” across its many interpretations. Aside from the plethora of pop culture references—Hollywood films, American punk bands, Luniz’s “I Got Five On It”—there’s something strictly American about “Us.” Within Peele’s premise the idea that inside of every American in 2019, whatever you believe in, is a sense of resentment. Peele’s screenplay is more literal, imagining that with the thousands of miles of abandoned tunnels and passageways mentioned in the credits, all Americans have a hateful version of themselves under the surface.

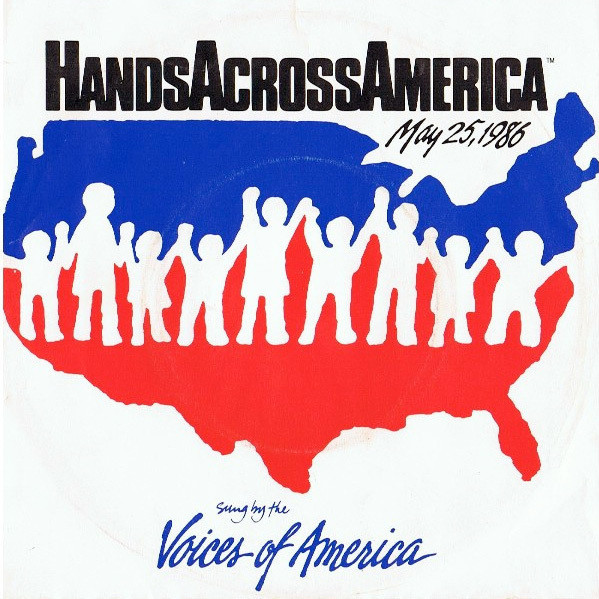

As a filmmaker whose imagination feeds equally off symmetry and open interpretations, the bookending shots of “Us” tell the whole story. There are many pop culture references in the movie, but the most important is front and center in the first shot. Surrounded by VHS copies of “C.H.U.D.” and “A Nightmare on Elm Street,” a TV plays an ad for Hands Across America. It speaks of the true event in 1986, in which millions of “Good Samaritans” would hold hands and “tether” themselves across the country, in an effort to fight homelessness and to show a sense of unity. The reference is an excellent deep cut from Peele, in part because Hands Across America failed, such an act then buried and forgotten within American pop culture.

Peele makes a doppelgänger for Hands Across America in his last shot, the scariest image in the entire film. After killing their above-ground selves, tethered individuals get in line and join hands, peacefully. United they stand across rolling hills, a silent majority in MAGA hat-red jumpsuits. This is Peele’s version of an apocalypse, and one of the most disturbing images post-2016 about the expansiveness of hatred that prevails over America.

For a movie that’s initially about the fear of recognizing your immediate selves, the meaning behind the tethered is a true Rorschach test (with reference to the film’s teaser poster) that’s open to many interpretations. Maybe to you it’s obviously about class, or the underprivileged, or the impact different generations, or our nation’s overall history. But in my eyes, the film’s final twist, about the switched lives of the two young girls, is the most revealing.

It becomes clear in the last few minutes that being born in the tethered does not mean you are without empathy. As Red’s full life story is revealed, we see that hatred like hers can be learned, that it can fester and be radicalized. To be tethered like Red became as a little girl is to be trapped in a claustrophobic space of swallowed fear, disorientation, and anger. It is a terrifying way to live. As Peele explains his idea of horror in Shudder’s excellent black horror documentary “Horror Noire,” “When I think about the fears that we deal with, I think that anything that we suppress as people, anything that we push down and hold deep, is going to explode. It’s gonna come out in a nasty way.”

The final act of “Us” presents a life of subsisting on purely those feelings, and we then witness such an unnatural, disturbing way of existence become weaponized and organized. Peele’s last twist has an incisive quality that’s incredibly emotionally abrasive—the loss of compassion for our main hero Adelaide, slamming next to a new understanding of the immense pain Red has inside of her. Peele then blows up that sense of tragedy on a massive visual scale, juxtaposing those life stories with an overwhelming spectacle of hate. “Us” argues, if not proves, that Hands Across America could only be achieved nowadays by values that are antithetical to love.

The sentiment has excellent timing—it is assuredly inspired by the 2016 election, while coming with a profoundly sobering warning for the 2020 elections. I see the bare white walls of the tethered and I think of those whose ideologies are steered by what they are afraid of, or the politicians and talking heads who stand in front of exaggerated crowd numbers and evangelize about imposing threats, caravans, leading to wars against info, creating conspiracies against institutions as broad yet vital as critical thinking. I see the hostility within the tethered, and I think about the recent study that was recently published by the Washington Post related to how the counties that hosted a 2016 rally for our current president saw “a 226% increase in reported hate crimes over comparable counties that did not host such a rally.”

In Peele’s previous film “Get Out,” a lovable TSA agent came to the rescue of his friend, and Peele spared movie audiences another image of an incarcerated black man. But “Us,” which is poised to become one of the most important horror titles in film history, offers Americans no such reprieve. Peele’s vision reckons with a force that feels unstoppable in America, especially if those who choose empathy lose their grasp of it. To quote former Nixon and Trump advisor Roger Stone: “Hate is a more powerful motivator than love.”

Nick Allen is the former Senior Editor at RogerEbert.com and a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association.