In the grand finale of “Captain Marvel,” our heroine, Carol Danvers (Brie Larson)—who has gone from a headstrong Ace fighter pilot to an amnesiac alien warrior to a renegade soldier reclaiming her humanity—finds herself prostrate before the Supreme Intelligence, the supposedly all-knowing leader of the Kree people, like an AI version of The Wizard of Oz. The Supreme Intelligence taunts her with her failures as a human woman back on Earth, a montage of her falling down again and again—at the go-cart track; at the baseball diamond; at the Air Force Academy; and in the sky, when she’s shot down and exposed to a Tesseract-infused energy core. But then Carol’s anger and determination conjures another reel of visions: She gets back up, every single time. The poignancy of her stubbornness inspires Carol to peel away the Kree inhibitor device from her neck and channel the full force of her powers. She becomes a warhead of a woman, dispatching an entire space armada in a fury of fiery kinesis—tossing earth-bound missiles into the galactic deep and punching through a hulking space cruiser—before finally confronting the Kree Accusers with a smirk and a fist that sends shockwaves through the cosmos.

The sequence is more than just the scrappy protagonist becoming a true hero. Like Tony Stark taking out the terrorist baddies sieging a poor village, or Steve Rogers liberating the POW camp where his best friend is being held, it has an undeniably symbolic potency. Carol—who has been told, as a woman on earth and a Kree on Hala, that her emotions make her impulsive and weak, that she must control herself to become a worthy pilot and a noble warrior—can only access her luminescent glory when she accesses her righteous and long-delayed rage. Women’s anger is finally being recognized as a political force, a comprehensive social reckoning, and its own genre across all forms of media, as driven and typified by the Strong Female Protagonist.

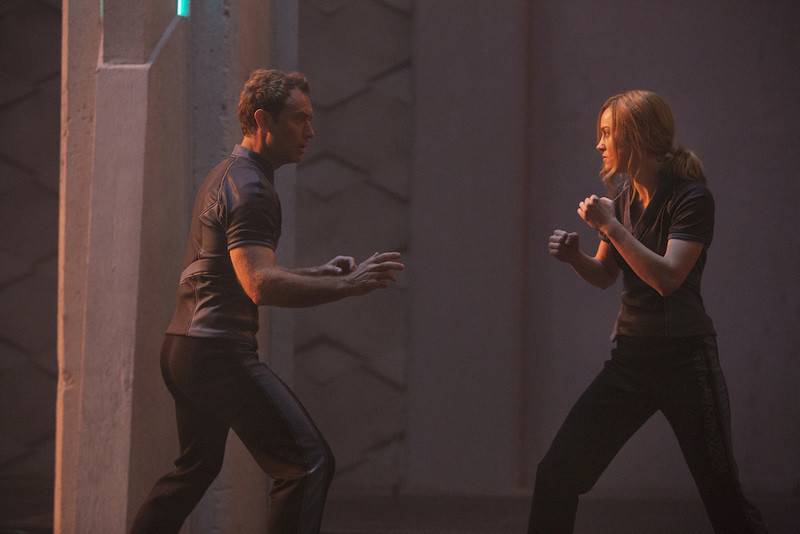

"Captain Marvel" certainly leans into these tropes, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Why shouldn’t little girls (and, ahem, adult women) enjoy the vicarious thrill of watching someone who looks like them soar “higher, further, faster,” when little boys have long been able to imagine themselves as the red-caped protectors of “truth, justice, and the American way”? But the film has a far more nuanced and complicated take on what authentic empowerment looks like. Carol’s arc leads her to that grand moment of cathartic intergalactic badassery; it is also, equally, about how she rejects the cosseted models of courage, strength, and power she learned under the tutelage of Yon-Rogg (Jude Law), her Kree commander—which have a spiritual symmetry with the more jingoistic messaging that contemporary women receive about becoming Boss Bitches and bad-asses and Head Bitches in Charge.

The aggressive earnestness of the second-wave feminist, and the spritely “girl power” and acerbic wrath of the riot grrl third-wavers, have calcified into a new ideal of empowerment that values a certain kind of toughness—a brash ability to dole out, and take, extreme amounts of violence; to punch against a glass ceiling with bloodied knuckles; and the fortitude to whittle the body and the mind into prime fighting form. There might seem like a canyon of daylight between Instagram influencers extolling girls to forsake the willowy waifs of yesteryear, load up on lean proteins and take up kickboxing because “strong is the new skinny,” the “let me tell you, girl” faux conspiratorial camaraderies of GirlBoss headlines like “Why ‘Follow Your Passion’ Isn’t Always the Best Career Advice,” and the extremity of organizations like the NRA trafficking in “you go girl-isms” through its “Refuse to Be a Victim” campaign and “The Power of Women” Leadership Forum (with an introductory video that features girl power platitudes like, “you don’t need all of these political people telling you how to defend yourself or live your lives, we’re women, our instincts will tell us everything we need to know.”)—yet they are all animated by a peppy jingoism that, ironically enough, supplants the real messiness and vulnerabilities of women’s lives with a mandate to be “empowered.”

Never mind that “strong is the new skinny” is still pretty damn skinny (unattainably skinny, for many of us), or that devoting one’s life and creative energies to becoming a shinier, more effective cog in a vast corporate machine shouldn’t be the most admirable goal, or that though gun violence is a leading cause of death for women (particularly in domestic violence homicides) no matter how thoroughly they pink-wash the bloodstains. Even most of Captain Marvel’s Strong Female Protagonist foremothers—like Sarah Connor pumping her shotgun with one well-muscled arm, Trinity mowing down a slew of faceless assailants in a balletic procession of gunfire, or even her sister in the MCU, Black Widow, who proves her mettle by subduing men twice her size (while wearing a cleavage-bearing catsuit, no less)—are largely defined by how much damage they can inflict. There is precious little sense of their personal investment in their fights, beyond some amorphous concept of “saving the world.” Their narrative arcs, like the narratives behind the current mode of “empowerment culture,” is about achievement and dominion, about being tough for toughness’ sake and ratcheting up easily-quantified victories.

"Captain Marvel" explicitly rejects these narratives. Yon-Rogg serves an avatar of the benevolent sexism that has tried to curtail Carol, and the beautiful wildness of her emotions and ambitions, under the guise of “her own good.” He is just like than Carol’s father, who snaps at her that she’s going to “kill herself” by racing at the go-cart track (though he lets the boys do it), or her colleagues at the Air Force who smugly mansplain that it’s called a “cockpit for a reason” and that she’d be a “great pilot and all” if she didn’t let her feelings “get in the way”—yet there’s something more subterranean, and insidious, about the way he positions himself as her mentor and ally. He trains her in the fine arts of hand-to-hand combat and tries to harden her for war, to make her an impassive soldier for the glory of all Kree; his litmus test for her to prove that she’s truly strong, truly capable, is for her to knock him down, mano a mano, sans her “light show.” He tells her, repeatedly, that the Kree vested her with her powers, and that their mission to hunt down and obliterate the Skrull scourge is a sacred one—both lies. The movie’s great twist is that the Kree are not, in fact, “noble warrior heroes,” but militaristic invaders whose only value is “might makes right.”

The Kree don’t give Carol her real power—just as the gym ads and hard-bodied action heroines, the career advice columns about “knowing your worth and asking for more,” the “fight like a girl” breast cancer awareness campaigns, and the pink handguns don’t give women real power. But they need her to believe that they do, just as “empowerment culture” needs women to believe that spending the money on Krav Maga classes and diet supplements; submitting themselves to a crass capitalist machinery that isn’t invested in ever helping them breathe the air outside that glass ceiling; accepting macho-lite sloganeering about “not being a victim” from an organization that propped up one of the virulently misogynistic administrations in recent history, is demonstrating how strong they are. It’s like complimenting the spit-shined perfection of the boot on our necks. Authentic empowerment can’t be hash-tagged or packaged in gym memberships. It doesn’t come from a promotion or in the squeeze of a trigger—it manifests at the ballot box or in front of a mirror, in a quiet yet insistent refusal to ever let anyone or anything make us feel inferior.

The Kree allow Carol to have a facsimile of her power, until she chooses to show the Skrull refugees compassion—then the Kree quite literally take that power away. Yet Carol conjures her innate, full, and dazzling power not by punching a litany of bad guys but when she remembers her own vulnerability, and who she was on earth: Not as some incredibly bad-ass fighter pilot (though she may be that), but as a willful child, a beloved friend and auntie. Her real superpower isn’t just that otherworldly energy that puts thunder in her fists and fire under her skin, it’s her beautiful stubbornness and her very human empathy.

While it may seem reductive to compare “Captain Marvel” with “Wonder Woman,” both films are remarkable for introducing a new kind of heroine, one who doesn’t showboat her power simply because she can—these women’s strength is in service of people who are weaker, who can’t fight for themselves. The Amazonians are certainly not the malevolent, imperialistic Kree, but Diana still must evolve beyond their isolationism, to fight “with love.” These movies can redefine what “girl power” can look like in more holistic, sustainable, and life-affirming ways. In “Captain Marvel,” Mar-Vell, who eschews the shallower ideals of ceaseless dominion to help vulnerable and displaced people, is the only noble warrior hero among the Kree. Carol takes that vision of a nurturing, protective strength higher, further, and faster.