Now streaming on:

I remember reading about the case at the time. A high school kid killed his girlfriend and left her body lying on the ground. Over the next few days, he brought some of his friends out to look at her body, and gradually word of the crime spread through his circle of friends. But for a long time, nobody called the cops.

A lot of op-ed articles were written to analyze this event, which was seen as symptomatic of a wider moral breakdown in our society. "River's Edge," which is a horrifying fiction inspired by the case, offers no explanation and no message; it regards the crime in much the same way the kid's friends stood around looking at the body. The difference is that the film feels a horror that the teenagers apparently did not.

This is the best analytical film about a crime since "The Onion Field" and "In Cold Blood." Like those films, it poses these questions: Why do we need to be told this story? How is it useful to see limited and brutish people doing cruel and stupid things? I suppose there are two answers. One, because such things exist in the world and some of us are curious about them as we are curious in general about human nature. Two, because an artist is never merely a reporter and by seeing the tragedy through his eyes, he helps us to see it through ours.

"River's Edge" was directed by Tim Hunter, who made "Tex," about ordinary teenagers who found themselves faced with the choice of dealing drugs. In "River's Edge," that choice has long since been made. These teenagers are alcoholics and drug abusers, including one whose mother is afraid he is stealing her marijuana and a 12-year-old who blackmails the older kids for six-packs.

The central figure in the film is not the murderer, Sampson (Daniel Roebuck), a large, stolid youth who seems perpetually puzzled about why he does anything. It is Layne (Crispin Glover), a strung-out, mercurial rebel who always seems to be on speed and who takes it upon himself to help conceal the crime. When his girlfriend asks him, like, well, gee, she was our friend and all, so shouldn't we feel bad, or something, his answer is that the murderer "had his reasons." What were they? The victim was talking back.

Glover's performance is electric. He's like a young Eric Roberts, and he carries around a constant sense of danger. Eventually, we realize the danger is born of paranoia; he is reflecting it at us with his fear.

These kids form a clique that exists outside the mainstream in their high school. They hang around outside, smoking and sneering. In town, they have a friend named Feck (Dennis Hopper), a drug dealer who lives inside a locked house and once killed a woman himself, so he has something in common with the kid, you see? It is another of Hopper's possessed performances, done with sweat and the whites of his eyes.

"River's Edge" is not a film I will forget very soon. Its portrait of these adolescents is an exercise in despair. Not even old enough to legally order a beer, they already are destroyed by alcohol and drugs, abandoned by parents who also have lost hope. When the story of the dead girl first appeared in the papers, it seemed like a freak show, an aberration. "River's Edge" sets it in an ordinary town and makes it seem like just what the op-ed philosophers said: an emblem of breakdown. The girl's body eventually was discovered and buried. If you seek her monument, look around you.

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

99 minutes

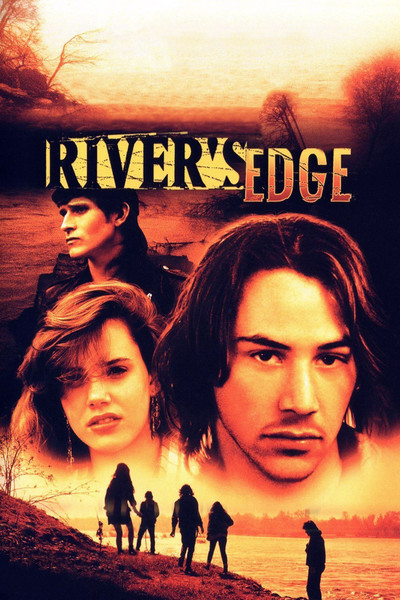

Dennis Hopper as Feck

Ione Skye Leitch as Clarissa

Daniel Roebuck as Sampson

Joshua Miller as Tim

Keanu Reeves as Matt

Crispin Glover as Layne

Roxanna Zal as Maggie