Lord Richard Attenborough, legendary director and actor, has passed away at the age of 91.

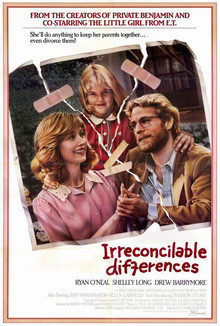

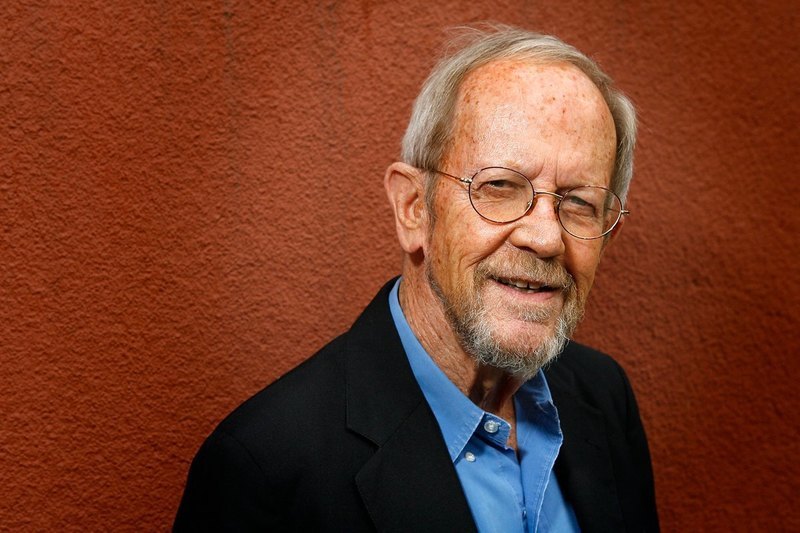

The first rule in Elmore Leonard's ten rules of writing is "Never open a book with the weather." It could never be a "dark and stormy night" in Leonard's universe. Instead, he opened his novels with nonchalant statements of character-driven fact. "Rum Punch" begins "Sunday morning, Ordell took Louis to watch the white-power demonstration in downtown Palm Beach." "The Hot Kid" informs us that "Carlos Webster was fifteen the day he witnessed the robbery and killing at Deering's drugstore." And "Glitz"'s opening line kicks off two and a half of Leonard's most readable pages with "The night Vincent was shot he saw it coming." Elmore Leonard got straight to the point. His characters were sometimes in love with their verbosity, but Leonard the narrator did not share this predilection. The omnipotent voice running through Dutch Leonard's work told you who said what, who did what, and the darkly comic repercussions of both. No writer wrung more color out of simply telling you what happened than Dutch Leonard. "Melanie was holding it in both hands now, arms extended, aimed at Gerald. "He tossed the shotgun to land on the sofa, looked up at Melanie and said 'Okay, now you put that down, honey, and I won't press charges against you.' Confident about it, as though it would settle the matter."Melanie didn't say anything. She shot him." –"Rum Punch"Leonard's characters were a multi-racial motley crew of cops, criminals, outlaws, lawyers, cowboys and sociopaths. They did not always follow the crime fiction novel's gender conventions. Strong, brutal women and weak, emotional men were not verboten. Leonard's characters were beholden to their own self-defined notions of ethics and morality. They were often much less clever than they thought; their flaws of nemesis underestimation became their undoing. Those who survived sometimes found themselves in other novels. Leonard never passed judgment as his characters flamed out in pitch black comic blazes both pathetic and glorious. To do so would violate his last and most important rule of writing: "Leave out the parts readers tend to skip." Much of the pleasure of reading Elmore Leonard was in the dialogue, which is why so many of his books became movies and TV series. Leonard followed his rule of "avoiding detailed descriptions of characters" by having his people talk to each other. He had an ear for the way conversations flowed, whether they were conducted on the street, in the precinct, or on the range. For a White guy, he certainly knew how to sound convincingly like the Black dudes who populated many of his novels. He captured the cadences of their speech, and did so without stereotype. His Brothers sounded like the guys I heard on the street in my old neighborhood; his cops sounded like cops I knew. Leonard embraced and elevated what they said, letting them ramble on whenever necessary. This love of casual chatter is probably what drew Tarantino to adapt "Rum Punch" as "Jackie Brown." It's certainly what made him pull entire chunks of Leonard's dialogue verbatim into the "Jackie Brown" script.The labyrinthine plots Leonard dragged his characters through were overly complicated yet always compelling. Even in something as spare and nasty as "52 Pick-Up," the first book of his I read, Leonard toyed with the expectations of where his stories took us. Even in the most convoluted plots, there was a feeling that the reader got entangled in this mess by virtue of the characters' machinations, not the author's. Before turning to the Florida-set crime stories that became his trademark, Elmore Leonard wrote Westerns. "3:10 to Yuma" and "The Tall T" were based on his work, as was Paul Newman's 1967 film "Hombre." Starting with "The Big Bounce" (made with Ryan O'Neal in 1969), Leonard changed his genre but kept many of the characteristics of a good Western. For example, "Mr. Majestyk" features a character protecting his "homestead" in much the same way as Jimmy Stewart or Randolph Scott would have. And of course, "Justified"'s Raylan Givens is the perfect synthesis of both genre halves of Leonard's work. Is there another author besides Shakespeare and Stephen King whose prolific output inspired so many movie adaptations? And by directors as varied as Abel Ferrara, Steven Soderbergh, Quentin Tarantino, Budd Boetticher, John Frankenheimer, Barry Sonnenfeld and Burt Reynolds (whom I'm sure Leonard wanted to shoot after seeing "Stick"). The stories vary from tales of Hollywood to big money heists to sleazy exploitation. Regardless of quality—and it varied from film to film—the spirit of Dutch Leonard's prose was felt by the viewer. Since I was 17, Elmore Leonard has been my favorite writer. I told him so the one time I met him. It was at the now defunct and long-gone Waldenbooks on Exchange Place and Broadway in Manhattan. He was there to sign copies of "Rum Punch," which was eerily prescient since it was the basis of my favorite film adaptation of Leonard's work. He was a very nice man, patiently listening to the 22-year-old aspiring writer whose excited rambling violated Leonard's fourth rule of writing ("Keep your exclamation points under control!"). When I was done, he verified the spelling of my name, signed my book and wished me luck with my writing.I hadn't thought about that meeting in a while, but when I heard that Leonard died today, it rushed back to me with the immersive force of a good Elmore Leonard set piece. There was casual chatter, a cool as a cucumber experienced character, and a matter of fact, straightforward rendering of events. Nobody got shot, which is a good thing for me, but that didn't make my run-in with Mr. Leonard any less memorable. Rest in peace, Dutch.

August 15 marks the 20th anniversary of the debut of "The Larry Sanders Show," episodes of which are available on Netflix Instant, Amazon Instant, iTunes, and DVD. This is the first part of Edward Copeland's extensive tribute to the show, including interviews with many of those involved in creating one of the best-loved comedies in television history.

by Edward Copeland

Over the course of my lifetime, I've watched a lot of movies -- an old computer contained a program with an editable database of titles and allowed for the addition of new films. Back when I used that PC, my total hovered in the thousands. "The Larry Sanders Show" produced a mere 89 episodes in its six season run from 1992-1998 that began 20 years ago tonight on HBO. "I know it sounds cliché but -- honest to God -- it seems like it was just about a week ago. It's so odd that it's 20 years," Jeffrey Tambor said in a telephone interview.

Despite the vast disparity between the quantity of films I've viewed and "Larry Sanders" episodes, when I recently took part in The House Next Door's "If I Had a Sight & Sound Film Ballot" series, I found it far easier to prune those pictures down to my ten favorites than I did when I applied the same task to "Larry Sanders" episodes. (Picking a clip or two from each show proved even more difficult as inevitably I'd want to include the entire half-hour.) Three or four episodes I knew had to be on the list, but then it got tough. I considered making a list of the best episode for each character such as the best Brian episode ("Putting the 'Gay' Back in Litigation"), the best Beverly ("Would You Do Me a Favor?"), the best Phil ("Headwriter"), etc. With all the priceless episodes centering on Hank and Artie, I imagined those two characters conceivably filling all ten spots alone.

A series that broke as much ground as "The Larry Sanders Show" deserves a grander tribute to mark the two decades since its birth than just a recounting of a handful of episodes -- and I had that intention. Unfortunately, my physical limitations and time constraints thwarted my ambitions. Rest assured though, that salute shall be forthcoming (MESSAGE TO BOB ODENKIRK: YOU STILL CAN TAKE PART NOW). As with any list, I'm certain my fellow "Larry Sanders" fans shall express outrage at my omissions (I already hear the shouts of "Where is the one with Carol Burnett and the spiders?" "No 'Hank's Sex Tape!' Hey now!"). Believe me, I'm as livid as you are and may join in the comments to give myself the thorough tongue-lashing I so richly deserve for these unforgivable exclusions. First, though, I'm going to fix myself a Salty Dog, using Artie's recipe of course. I want to be able to grab those olives, not fish for them. So, for good or ill, I submit my selections for my ten favorite episodes of "The Larry Sanders Show." Since bestowing ranks only leads to more trouble, I present these ten in chronological order:

This story, found at last, has been long lost in the remote recesses of the Sun-Times archives. I wrote it for Midwest magazine, the paper's old Sunday supplement. For easier reading, there is a plain text version just below.

By Roger Ebert Holmby Hills, California

I. THE ACTUAL WILD GAME

The grounds, I was assured by a Playboy public relations man, make up a 5.1-acre compound. The site is surrounded by a brick fence, penetrated at two points by winding roads which are each three-quarters of a mile in length, one having to wind a bit more than the other to achieve that distance.

Inside the brick wall, he said, "is an actual forest, an actual wooded forest composed of giant redwood trees, and actual wild game roams in the actual park."

Wild game? I said. What kind of wild game?

"We don't know," he said.

You never do, do you? Wasn't it H. P. Lovecraft who suggested that one never knows, really, what lurks in the woods, gathering strength there in the dampness and dark, preparing for the day when it will spring out and gobble up children and little bunny rabbits? Yes.

I imagine maybe one of the first things Hugh Hefner will want to do, after he gets really settled in the Playboy Mansion West, will be to gather about him a hardy band of cronies and stage a safari through that 5.1-acre actual wooded area, identifying, where possible, the wild game that roams there. It will have to be a camera safari, of course, since one is not allowed to discharge firearms within Los Angeles County itself.

II. THE GREENING OF THE RAIN DRAINS

The mansion, I was told, has been appraised at $2 million including the grounds, the two greenhouses and the gardener's cottage. The furnishings are worth another $500,000. The place was designed in 1927 by an architect named Arthur Kelly, who specialized in mansions for the very rich. The difference between the very rich and you and me is that their mansions don't look like other people's mansions.

The mansion was occupied first by a man named Arthur Letts Jr., heir of a department store owner. It belonged most recently to Louis Statham, of the Statham Instruments. For the last 4 1/2 years, it has served as the unofficial hospitality residence of the City of Los Angeles, and the king and queen of Thailand have stayed there.

The mansion has 30 rooms and has been described as sort of Tudor Gothic or, according to Joyce Haber, a cross between Forest Lawn and "The Phantom of the Opera." But to be more specific, the Playboy public relations man painted a word-picture for me:

"It is a handcrafted fortress, with walls 18 inches thick made from reinforced concrete and stone. It has a slate roof, it has turrets, all kinds of turrets in the house, and archways, there's archways all over the place. Doors of golden oak, band-hewn. The rain drains have a kind of a little greenish tint to them because of the age, looking very, very rustic.

You enter the mansion through giant golden oak doors that swing right into the mansion's Great Hall, which is a very great hall. A shimmering crystal chandelier hangs overhead, and when you open the front door and walk in, you step right on an Italian marble floor. Windows extend from the floor to the ceiling... oak paneling is all around you... a Grand Staircase, the focal point of the Great Hall, consists of two separate sets of stairs that are curved from the main level right up to the upper level, forming a sloping, graceful arch, and, hanging right in the middle, there is a very many-tiered chandelier..."

III. WHAT TO DO ABOUT THE CATERPILLARS?

On the evening after the Academy Awards ceremony, I stepped through the band-hewn golden oak doors and paused for a moment on the Italian marble floor. My eyes lifted briefly to the many-tiered chandelier, and then rested on the Grand Staircase, where an assortment of Hefner's guests reclined on the stairs and watched the new arrivals.

This was Hefner's official housewarming for Playboy Mansion West, and there were two bands, two tents (one indoors, one outdoors) and a fire in the fireplace in every room. I walked through the Great Hall and found myself outside the mansion again, in the outdoor tent, where a band was playing and people were lined up three deep at the bar. Over in the distance, beyond the tent, giant orange Caterpillar earthmoving equipment was outlined against the night sky, with floodlights on them. I wandered back inside, and found myself in the living room, or one of the living rooms, talking to Jon Anderson, the columnist.

"Are you writing about this?" he said.

I guess so, I said.

"On deadline, or..."

No, I said, I'll be doing it for Midwest. Probably won't appear for a month or so.

"Good," said Jon. "Then I can show you something."

He led me across the room to the giant fireplace and pointed above it. There was a large reproduction of the "Mona Lisa" on the wall, done in needlepoint with a gold plaque underneath that said, "Barbi Benton - 1970."

Isn't that something, I said.

"We're going to use it in our column," Jon said. "It adds a nice, homey touch to the place, don't you think?"

Sure does, I said. Wilt Chamberlain's belt buckle passed by at eye level.

"It looks like one of those paint-by-number things, only in needlepoint," Jon said.

Wilt Chamberlain certainly is tall, I said.

"Needle-by-number," Jon said. "Or... point-by-point."

I wonder how long it took her, I said.

"It looks pretty complicated," Jon said. "The smile alone..."

Yes, I said, just the smile alone...

"Have you seen her?" Jon said.

Who?

"Barbi."

Not yet, I said. Just then Hugh Hefner himself walked into the room and nodded at everybody.

"Wonderful party, Hef," Jon said.

"Glad you're enjoying yourself," Hefner said. "We were worried right up to the last minute that we'd invited too many people. Then somebody came up with the inspiration of the outside tent, to handle the overflow. Now things are going great."

We nodded, and the three of us looked round the living room. Guests and bunnies and girls you vaguely recognized as former Playmates were all sitting around and, apparently, having great times. Big piles of floor-pillows were stacked here and there, but most everybody was sticking to chairs.

"The one problem with the outside tent," Hefner said, "was what to do about the bulldozers."

I was wondering about them, I said.

"We're digging a swimming pool back there," Hefner said. "Somebody said we should put potted trees in front of them, camouflage them somehow, but we finally decided, the hell with it, why not light them up as modem art or something. So that's what we did."

Somebody grabbed Hefner by the arm to introduce him to fresh guests, and Jon and I wondered back out onto the patio.

"Five centuries of art," Jon said.

What?

"From the 'Mona Lisa' to the Caterpillar."

Which one, I said, do you think will turn into a butterfly first?

"Hard to say," said Jon.

IV. TWO MALE LIONS

I left the tent and strolled alone through a portion of the 5.l-acre grounds. Stone walks surrounded the house, and from the front you could hear the excitement of new arrivals, pouring out of their limousines and Yellow Cabs and hurrying through the giant golden oak doors.

My steps led me some distance from the house, and the sound of the rock band came drifting to me...

Rap... rap... rap... they call him the rapper...

Something caused me to think about a character I hadn't thought of in some time, the Great Gatsby. There's a scene in that novel by Fitzgerald telling of the almost nightly arrival of fresh carloads of guests, all eager to share Jay Gatsby's fabulous hospitality, and to glory in his famous home. Later on in the novel, Gatsby's hospitality comes to a sudden end, but not all the guests get the word, and for several weekends thereafter, cars continue to come out from the city and pull into the silent driveway, and then leave when they see there's no party.

At any given moment in history, I decided, there is a man whose job it is to give famous parties. Sometimes he is a fictional person, sometimes he is real. Sometimes he is the Great Gatsby, sometimes William Randolph Hearst, or Hugh Hefner...

Coming back toward the house, I found myself suddenly in the presence of two stone lions. They flanked a short flight of steps and gazed back toward Los Angeles. They both had manes, which meant they were both males. I decided their names were Bill and Hugh, Bill on the right looking over somewhat curiously at his neighbor.

V. TWO MORE MALE LIONS

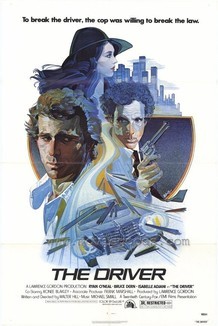

Back inside the tent, Ryan O'Neal was leaning against the bar with a drink in his hand and looking out over the tables to the dance floor at the other end of the tent. There was something in his look that seemed peculiar until I got it figured out. Then it seemed understandable enough. Ryan O'Neal wasn't looking out over the crowd. He was in the act of being Ryan O'Neal looking out over the crowd. Does that make any sense? What I mean is, he wasn't really looking; he was aware of himself as Ryan O'Neal, being seen to be looking.

That doesn't say it either, but the hell with it. The fourth lion was Jim Brown, who moved through the crowd with a kind of dangerous grace, attracting a great deal of attention even though he was apparently doing nothing to inspire it. People, were wondering, I suppose, whether he had really thrown that girl off the balcony, etc.

Some people occupy space differently than others. Jim Brown encloses space while Ryan O'Neal merely fills it.

VI. TWICE AS BIG AS ILLINOIS

There were girls everywhere, but they seemed to be filling space like Ryan O'Neal and not like Jim Brown. It occurred to me that a lot of the girls you see at parties like this lack some dimension, the third or the fourth, maybe. They are pretty and they smile, but they're girls, not women.

Why? Because they lack the final measure of self-confidence to be women, I think. The Playboy girl is a commodity, to some degree; she is an image to be packaged and merchandised, as much of a symbol as a Chevrolet or a Baggie. Her success depends upon your acceptance of her. If you like her, if she "turns you on," then she has succeeded. But if she doesn't, then she's failed as everything: Girl, symbol, commodity.

A girl who is uncertain at her core can never be really interesting, no matter how beautiful she may appear to be on the surface. She isn't really there, and that fact frightens her. There were some real women there. Polly Bergen and Edy Williams (two names you might not have expected to come across on the same list) had that dimension. You felt they were people, and knew they were people. But a lot of the Bunnies seemed oddly transparent.

Some people have the notion that a Hefner party is sexy and sensuous and the next thing to a genteel sort of orgy. Hefner's parties are fun, but in an entirely different way than the image would suggest. The food is good, the booze is free and keeps coming, and there are sure to be interesting people there. It's just that, somehow, all these people who look like such good friends when Playboy runs a layout about a Hefner party aren't good friends - have probably just met tonight - and are having a conventionally good time. We've all read about that little room behind the waterfall in Hef's Chicago swimming pool, but what good is the little room when people inside it are clearly visible? A Hefner party is like that little room: You swim beneath the waterfall, but, inside, the lights stay on.

And so, finally, the conversation gets around to Hefner himself (the conversational obsession at most of his own parties), and you wonder whether this turns him on, and how much he enjoys it. My private notion is that he enjoys it a lot; who wouldn't? If I had his fortune, I'd throw parties all the time for my friends. Wouldn't you? I think throwing the parties would be more fun than attending them.

Perhaps that's at the core of Playboy Mansion West: Now there can be great parties in California, just as there have been for years in Chicago, and all of this year's Hollywood people can come and mingle and talk, be photographed by the omnipresent Playboy photographers, eat expensive beef, watch the shrimp cocktail bowl being constantly replenished, name their brand of Scotch, wonder who everybody else is (and who they are) and try not to think about the stone lions.

Wondering down the Grand Staircase, I passed two guests who were talking about the Mansion West.

"How does this place stack up with his other place?" the first guest said.

"This one is twice as big as Illinois" said the second.

"It must be great to have two places," said the first.

"Better than only having one," the second said.

VII. INTRODUCTION IN THE FORM OF A SEQUEL

All these things and thoughts occurred the night after the Academy Awards. On the night before the Academy Awards, there was a big party at Le Bistro, the famous Beverly Hills club.

Hefner came with Barbi on his arm and seemed to be having a great time. Edward G. Robinson, who was also there, offered Hefner some pipe tobacco that, Robinson said, acted as an aphrodisiac. Hefner and Robinson shared a good laugh over that, and then Hefner moved easily through the room, talking to people. The party was crowded and noisy, and there was a band and lots of good things to eat and drink. But by 11 o'clock or so the people started to drift away (they don't stay up late in Hollywood; they're home by midnight, usually).

Hefner and Barbi left, and then there were maybe only 20 people remaining; the hard core who had negotiated special arrangements with the waiters to bring the booze to the table in bottles, not glasses, to save time. This group talked for 45 minutes or so while the waiters stood by and waited patiently for the party to finally be over. And then Hefner and Barbi came back into the room.

Didn't you already leave? somebody said.

"We took off, but then we thought we'd come back and see if there was still anything happening," Hefner said.

In reading "The Great Gatsby," I've sometimes had the notion that one of those great limousines that came out from the city, and paused in Gatsby's quiet driveway before driving away, was driven by Gatsby himself.

More than 150 of my other special pages are linked in the right column. var a2a_config = a2a_config || {}; a2a_config.linkname = "Roger Ebert's Journal"; a2a_config.linkurl = "http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/"; a2a_config.num_services = 8;

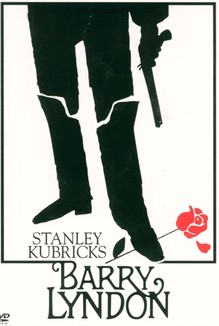

"Barry Lyndon": Let's begin again...

Some great (and maybe not-so-great) movies reward repeated viewings; others you may savor only once or twice. The newly redesigned Slate.com has asked several movie people what movies they've seen most often. (On my own personal list: I never tire of the crackling artistic life in "Nashville," "Chinatown," "Citizen Kane," "E.T.," "North By Northwest," "Trouble in Paradise," "Fight Club," "Donnie Darko," "Double Indemnity," "Stranger Than Paradise," "Stop Making Sense"... Then there's "Animal Crackers," any Buster Keaton movie [but especially "Our Hospitality," "Sherlock Jr." and "Steamboat Bill Jr."], "Waiting for Guffman," "Dazed and Confused," "Boogie Nights" -- oh, and "Kids in the Hall: Brain Candy," an unheralded comedy masterpiece...)

Among the choices in Slate's "The Movies I've Seen the Most":

Writer-director Paul Schrader (author of the indispensible book of film criticism, "Ozu Bresson Dreyer"): Robert Bresson's "Pickpocket." (Duh -- he's used the ending twice in his own movies, "American Gigolo" and "Light Sleeper.")

PARK CITY, Utah-- "Somebody asked me today, do I like acting?" Al Pacino was saying. "That stopped me. I had never been asked that." What did you say?

CANNES, France--John Sayles has two movies in release these days, but he takes a credit on only one of them. "Limbo" is his Cannes premiere, going into U.S. release on Friday. It's a story set in Alaska, that starts as a romance and ends as a cliff-hanger. And the other movie, which you may also have heard of, is "The Mummy."

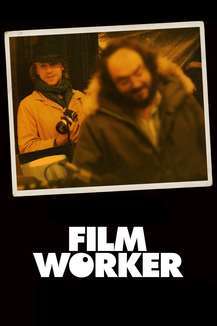

Stanley Kubrick, one of the greatest of film directors, and perhaps the most independent and self-contained, is dead at 71. The creator of "2001: A Space Odyssey" died early Sunday morning at his country home north of London.

PROVINCETOWN, Mass. -- Not far down the street there has been a bloody fist fight, two men pounding each other senseless over a woman, blood on the sidewalk, the police involved, but Norman Mailer hardly hears of it, he is so engrossed in the movie he is directing.

Did I see that TV documentary about John Ford? Yeah, I saw it." Peter Bogdanovich looked slightly nauseated. "Did I ever see it! Say I disliked it very much. No. Say I loathed it."

Calling yourself the author of the year's biggest novel,'' Erich Segal said, "is like calling yourself the world's greatest newspaper. It makes it sound like nobody else will say it for you, so you gotta say it for yourself . . . "