Inside many superhero stories is a Greek tragedy in hiding. There is the godlike hero, and he is flawed. In early days his weaknesses were simplistic, like Superman's vulnerability to Kryptonite. Then Spider-Man was created as an insecure teenager, and comic books began to peer deeper. Now comes the "Watchmen," with their origins as 1940s goofballs, their development into modern costumed vigilantes, and the laws against them as public nuisances. They are human. Although they have extraordinary physical powers, they aren't superheroes in the usual sense. Then everything changes for Jon Osterman, remade after a nuclear accident as Dr. Manhattan. He isn't as human as Batman, but that can be excused because he isn't human at all.

He is the most metaphysically intriguing character in modern superhero movies. He not only lives in a quantum universe, but is aware that he does, and reflects about it. He says, "This world's smartest man means no more to me than does its smartest termite." He lives outside time and space. He explains that he doesn't see the past and the future, but he does see his own past and his own future. He can apparently go anywhere in the universe, and take any shape. He can be many places at the same time, his attention fully focused in each of those places. He sees the big picture, and it is so vast that it's hard for him to be concerned about the fate of the earth.I wonder how many audience members will know much about quantum mechanics. Some will interpret it simply in terms of Dr. Manhattan's powers. It's one of those story devices like the warp drive in "Star Trek." Dr. Manhattan, however, views it in a much more complex way, from the inside, and apparently in terms consistent with current science. So let's ask what we understand about quantum mechanics. We'll start with me. I understand nothing.

Oh, I've read a lot about it. Here is what I think I know: At a basic level, the universe is composed of infinitesimal bits, I think they're called strings, which seem to transcend our ideas about space and time. One of these bits can be in two places at once, or, if two bits are at a distance, can somehow communicate with one another. Now I have just looked it all up in Wikipedia, and find that not only don't I understand quantum mechanics, I don't understand the article either. So never mind. Let's just say my notions are close to the general popular delusions about the subject, and those are what Dr. Manhattan understands.

Oh, I've read a lot about it. Here is what I think I know: At a basic level, the universe is composed of infinitesimal bits, I think they're called strings, which seem to transcend our ideas about space and time. One of these bits can be in two places at once, or, if two bits are at a distance, can somehow communicate with one another. Now I have just looked it all up in Wikipedia, and find that not only don't I understand quantum mechanics, I don't understand the article either. So never mind. Let's just say my notions are close to the general popular delusions about the subject, and those are what Dr. Manhattan understands.

So. I've just come from seeing "Watchmen" a second time, this time on an IMAX screen, which was an awesome experience. Not having read the graphic novel, I found my first viewing somewhat confusing. There were allusions and connections I suspected I was missing. I had to think back and take inventory of the characters. On the second viewing I was better prepared, and found the movie does make perfect sense on the narrative level. It takes place in 1985 in an alternate timeline, where Richard Nixon is still president, we won in Vietnam, Dr. Manhattan took the photo of Aldrin and Armstrong planting the American flag on the Moon, and so on. When the helicopters made their fateful flight to "March of the Valkyries" in "Apocalypse Now," Dr. Manhattan was there too.

The plot (very) briefly. In1985, America and the USSR are at the brink of nuclear war. Perhaps the Watchmen could save the planet. But someone seems to be trying to kill them, retired though they may be. This danger inspires them to reunite for the first time in years. On the second viewing, I realized something I missed the first time through: The Watchmen assassination plot makes no sense, because the only Watchman who could possibly save the planet is Dr. Manhattan, and his disinterest is cosmic. There is only one of the other Watchmen who might possibly persuade him.

The second time through I found myself really listening to what Manhattan says, and it is actually thought-provoking. I didn't care as deeply about the characters on the human level as I did with those in "The Dark Knight," but I cared surprisingly about the technically inhuman Manhattan. He doesn't lack emotion as the alien did in the recent remake of "The Day the Earth Stood Still." He has simply moved far, far beyond its reach. From where he stands, he might as well be regarding a termite. Why does he even bother to make love with Laurie Jupiter? Not for his own pleasure, I'm convinced. And not to father a Little Manhattan, either, because as I understand his body he would ejaculate only energy. Could be fun for Laurie, but no precautions needed, except not to be grounded at the time.

A spoiler follows. At the end of "The Day the Earth Stood Still," the alien decides not to destroy life on earth because he is convinced that humans do love one another. Nothing that sentimental motivates Manhattan. Listen carefully to what he says. He tells Laurie she exists because, "your mother loves a man she has every reason to hate, and of that union, of the thousand million children competing for fertilization, it was you, only you, that emerged. To distill so specific a form from that chaos of improbability, like turning air to gold!" He is intellectually amazed by her uniqueness, and by the workings of genetics. Her father and mother, were the last two people you expect, and from their unlikely coupling Laurie, specifically Laurie and no one else, was created. Manhattan is not saying he may save the planet because Laurie is so wonderful. He is saying he may save the planet because of the sheer wonder of the workings of DNA.

Safe now to read again. The next detail is not important to the plot of "Watchmen," but I found it fascinating: Manhattan thinks he might leave this planet altogether, travel to a distant galaxy, and there, he suggests, might try his hand at creating some life himself. He would then, would he not, be the Intelligent Designer of life in that place?

Left unanswered is the question of how life was created here on this planet, and indeed the question of whether Manhattan as he now exists constitutes life. Always remaining is the much larger question, Why is there something instead of nothing? These are questions Manhattan might fruitfully meditate upon, although if you exist on a quantum level, as he himself observes, life and non-life are all the same thing, just nanoscale bits of not much more than nothing, all busily humming about for reasons we cannot comprehend. As he puts it, "A live body and a dead body contain the same number of particles. Structurally, there's no discernible difference. Life and death are unquantifiable abstracts. Why should I be concerned?"

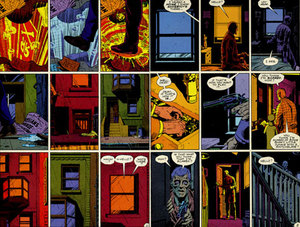

Whoa. I have come all this way, and forgotten all the things I meant to say about "Watchmen," its visual strategy, its acting, and so on. I know from many reports that the film is unusually faithful to the graphic novel written by Alan Moore and drawn by Dave Gibbons, importing some dialogue and frames literally. Faithfulness in adaptation is not necessarily a virtue; this is a movie and not a marriage. But I think it has use here, because it helps to evoke the film noir vision which so many comic-based movies inhabit. Looking at page grabs from the book, I can see Gibbons' drawing style is often essentially storyboarding.

The acting? Very effective. Yes, these characters are preposterous, beginning with their need to wear costumes and continuing with their willingness to retire them. But within the terms of the story and the screenplay by David Hayter and Alex Tse, the performances create a certain poignancy. These are not superheroes with human flaws. They are flawed humans all the time--some of them possibly mad (Rorschach is "crazier than a snake's armpit," a cop says.)

You can see Matthew Goode, as Ozymandias, using an interesting tactic: He adopts a manner that leads us to think one thing about him at the first, and another thing later. Jackie Earle Haley, as Rorschach, the raspy narrator, is tortured both in and out of his mask. Patrick Wilson (Nite Owl) needs his costume to even really even possess a personality. And so on, including Malin Akerman as Laurie, whose affection for Manhattan seems oddly plausible under the circumstances.

The graphic novel as storyboard

The graphic novel as storyboard

Zack Snyder's "300" (2006) showed a similar mastery of CGI imagery as "Watchmen" does. Most of both films is not really there. But "300" struck me as fevered overkill, literally; there wasn't a character I cared about. It involved, I wrote, "one-dimensional caricatures who talk like professional wrestlers plugging their next feud." In "Watchmen," maybe it's the material, maybe it's a growing discernment on Snyder's part, but there's substance here.

On a conventional screen "Watchmen" will have considerable power, so don't be at all reluctant to see it that way. If there was ever a film not intended to be seen for the first time on DVD, this is that film. But IMAX intensifies Snyder's visual strategy and the cinematography of Larry Fong. In its sometimes grungy way, it's beautiful. And look at the way Snyder creates its most spectacular artifact, Manhattan's crystal structure on Mars that seems to be a timepiece without hands--or time. Of course it's made with CGI and of course it looks phony. But after all, it isn't really there.

Manhattan's Hamlet's soliloquy

Dr. Manhattan's case study, by James Kakalios, author of The Physics of Superheroes

Quantum mechanics : "You and I do not exist"

Quantum mechanics made relatively clear

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.