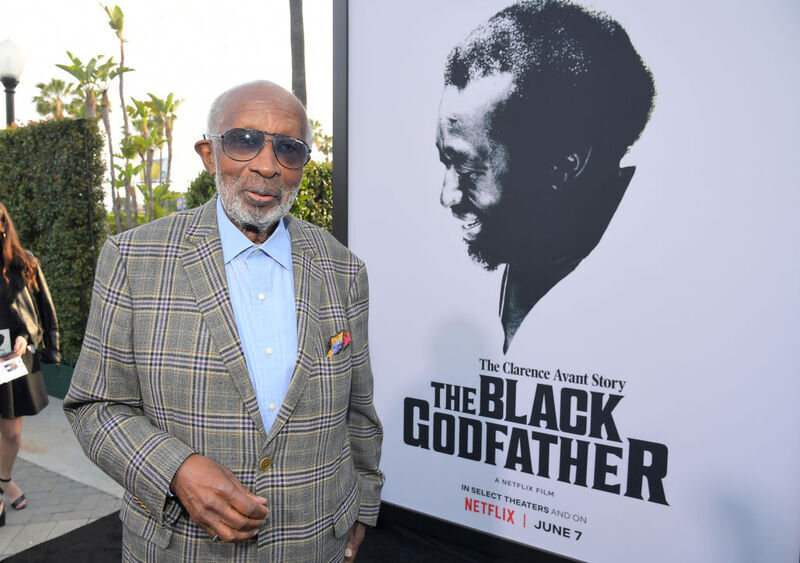

A tribute to Clarence Avant, the Godfather of Black Entertainment, who passed away on August 13th, 2023 at age 92.

A feature on Sidney Poitier's earth-shaking turn in In the Heat of the Night.

A look at the films most likely to be nominated for Best Picture.

A look at who could be nominated for Best Director at the upcoming Oscars.

Matt writes: In the sixth edition of RogerEbert.com publisher Chaz Ebert's "My Happy Place" series, she shares various ways we can each find joy during the 2020 holiday season when under lockdown.

A news story highlighting the films in the Black Perspectives program, including acclaimed works like Bad Hair, One Night in Miami, MLK/FBI, and Farewell Amor.

A tribute to the legendary B-movie writer and director, Larry Cohen.

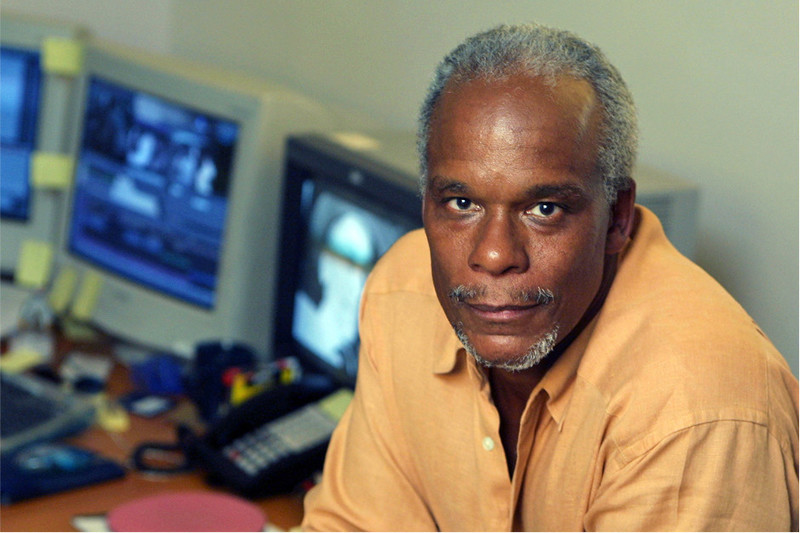

An interview with Stanley Nelson, the director of The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution.

With his perfectly styled Afro, cool bop walk and smart-aleck mouth, martial artist and actor Jim Kelly, who died from cancer on Saturday at the age of 67, was a seventies screen sensation who became an icon. Michael A. Gonzales appreciates cinema's first African-American martial arts star.

"The Girl" premieres on HBO at 9:00pm (8:00pm Central) on Saturday, Oct. 20. It will also be available on HBO GO.

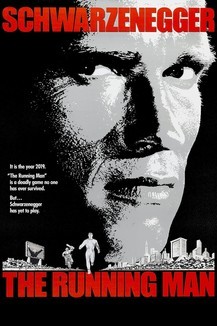

By Roger Ebert

I met Charles Bronson in New York City, where he was working once again with Michael Winner Winner, who also directed him in "Chato's Land," "The Stone Killer," and "The Mechanic." The new movie was "Death Wish," about a middle-aged New York architect who is repelled by violence until his own daughter is raped and his wife murdered. Then the architect becomes an instrument of vengeance. He goes out into the streets posing as an easy mark, and when muggers attack, he kills them.

"Death Wish" was being shot in New York in late, bitterly cold February night, and for openers I observed that the character seemed to have the same philosophy that's been present in all of Bronson's work with Winner: He is a killer (licensed or not) with great sense of self, pride in his work, and few words.

Bronson had nothing to say about that "I never talk about the philosophy of a picture," he said. "Winner is an intelligent man, and I like him. But I don't ever talk to him about the philosophy of a picture. It has never come up. And I wouldn't talk about it to you. I don't expound. I don't like to over talk a thing."

We are in the dining room of a Riverside Drive apartment that is supposed to be the architect's home in the movie. Bronson is drinking one of the two or three dozen cups of coffee he will have during the day and, having rejected philosophy, seems content to remain quiet.

Could it be, I say, that it's harder to play a role if you talk it out beforehand?

"I'm not talking in terms of playing a role," Bronson said. "I'm talking in terms of conversation. It has nothing to do with a role at all. It's just that I don't like to talk very much."

He lit a cigarette, kept it in his mouth, exhaled through his nose, and squinted his eyes against the smoke. Another silence fell. All conversation with Bronson has a tendency to stop. His natural state of conversation is silence.

Why?

"Because I'm entertained more by my own thoughts than by the thoughts of others. I don't mind answering questions. But in an exchange of conversation, I wind up being a pair of ears."

On the set, I learned, he doesn't pal around. He stays apart. Occasionally he will talk with Winner, or with a friend like his makeup man, Phil Rhodes. Rarely to anyone else. Arthur Ornitz, the cinematographer, says. "He's remote. He's a professional, he's here all the time, well prepared. But he sits over in a corner and never talks to anybody. Usually I'll kid around with a guy, have a few drinks. I think there's a little timidity there. He's a coal miner."

Later in the day, Bronson is sitting alone again. I don't know whether to approach him; he seems absorbed by his own thoughts, but after a time he yields. "you can talk to me now. I wouldn't be sitting here if I didn't want to talk. I'd be somewhere else."

I was wondering about that.

"I had a very bad experience on the plane in from California yesterday. There was a man on the plane, sitting across from me, and they were showing an old Greer Garson movie. He said, Hey, why aren't you in that? The picture was made before I even became an actor. I said, Why aren't you? I think I made him understand how stupid his question was.

"When I'm in public, I even try to hide. I keep as quiet as possible so that I'm not noticed. Not that I hide behind doorways or anything ridiculous like that, but I hide by not making waves. I also try to make myself seem as unapproachable as possible."

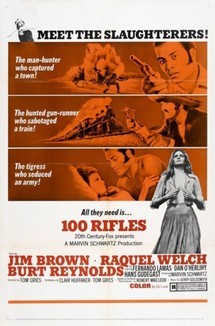

More silence. Phil Rhodes, the make-up man, is leafing through a copy of Cosmopolitan. Suddenly he whoops and holds up a centerfold of Jim Brown.

"Will you look at this," he says.

"Would you ever do anything like that, Charlie?"

"Are you kidding?" Bronson said. "What a bunch of crap. Look at that. Old Jim. People are so hung up on sex."

And, inexplicably, that sets Bronson talking "I've been trying to make it with girls for as long as I can remember," he says. "I remember my first time. I was five and a half years old, and she was six. This was in 1928 or 1929. It happened at about the worst time in my life. We had been thrown out of our house . . ."

The house was in Ehrenfeld, known as Scooptown, and it was a company house owned by the Pennsylvania Coal and Coke Company. When the miners went out on strike, they were evicted from their homes, and the Buchinsky family went to live in the basement of a house occupied by another miner and his eight children. "This would have been the summer before I started school," Bronson says. "I remember my father had shaved us all bald to avoid lice. Times were poor. I wore hand-me-downs. And because the kids just older than me in the family were girls, sometimes I had to wear my sisters' hand-me-downs. I remember going to school in a dress. And my socks, when I got home sometimes I'd have to take them off and give them to my brother to wear into the mines.

"But, anyway, this was a Fourth of July picnic, and there was this girl, six years old. I gave her some strawberry pop. I gave her the pop because I didn't want it; I had taken up chewing tobacco and I liked that better. I didn't start smoking until I was nine. But I gave her the pop, and then we . . . hell, I never lost my virginity. I never had any virginity."

He remembers Ehrenfeld well, and has written a screenplay with his wife Jill Ireland about life in the mining towns. He worked in the mines from 1939 to 1943, and getting drafted, he says, was the luckiest thing that ever happened to him: "I was well fed, I was well dressed for the first time in my life, and I was able to improve my English. In Ehrenfeld, we were all jammed together. All the fathers were foreign-born. Welsh, Irish, Polish, Sicilian. I was Lithuanian and Russian. We were so jammed together we picked up each other's accents. And we spoke some broken English. When I got into the service, people used to think I was from a foreign country."

Five boys in his family were drafted into the Army. An older brother, the one who took him into the mines for the first time, was part of the European invasion. "He was a Ranger, and he won a medal," Bronson said. "He was under fire constantly. And he said he'd rather do that than go into the mines again."

Bronson would not talk about his hometown screenplay, called $1.98, except to say it was fundamentally a love story with a mining town as the environment, but the next afternoon he met with two VISTA workers to discuss possible locations in Appalachia for the film. The towns he had scouted, he told them, looked too good. There were streets, there were lawns where things grew . . .

"I remember the old company towns. There was no neon, except for the company store. Nothing was green. The water was full of sulphur. There was nothing to put a hose to. There were unpaved streets covered with rock and slag. You had the rock dumps always exploding. They were always on fire, down inside, and if it rained for a long enough time, the water would seep down to the fires and turn to steam and the dump would explode."

The VISTA volunteers asked if Bronson's movie would deal with black lung disease.

"No, it's a love story. But it will be . . . beneficial to the miners, I hope. Right now it isn't a finished script. There are too many empty, dull places. And it's naive. But it will be accurate about mining. You had a feeling about mining. It was piecework; you didn't get paid by the hour, you got paid by the ton, and you felt you were the hardest-working people in the world.

"When I worked, the rate was a dollar a ton. You spent one whole day preparing so you could spend the next day getting it out. The miners felt bound together; they knew how much they could get out, how much they could do. And they worked. With the new machines, it's easier. Not more pleasant, but easier. But in those days, that was pure work. It wasn't a man on a dock with a forklift or any of that bullshit. It was pure work."

After the war Bronson went back home, but not to the mines. The veterans were given three months, he recalled, to decide if they wanted their old jobs back. Bronson did not. He picked onions in upstate New York, and then got his card in the bakers union. He worked on an all-night shift at a bakery in Philadelphia and took art classes in the evenings. He decided he knew more about drawing than the instructor did. He dropped the classes and quit his job (he still holds cards in both the miners and bakers unions), and went to New York City with the notion that he might try acting. Why acting?

"It seemed like an easy way to make money. A friend took me to a play, and I thought I might as well try it myself. I had nothing to lose. I hung around New York and did a little stock-company stuff I wasn't really sure at that time if l even wanted to be an actor. I got no encouragement. I was living in my own mind, generating my own adrenaline. Nobody took any notice of me. I was in plays I don't even remember. Nobody remembers. I was in something by Moliere - I don't even know what it was called.

"I have no interest in the stage anymore. From an audience point of view, it's old-fashioned. The position I've been in for the last eight years, I have to think that way. I can't think of theater acting for one segment of the population in just one city. That's an inefficient way of reaching people."

After New York, he tried the Coast. Spent some time at the Pasadena Playhouse. Got his first movie role in You're in the Navy Now because he could belch on cue, a skill picked up during Ehrenfeld days. He worked for years as the heavy, the Indian, the Russian spy. He had two TV series, "Man with a Camera" and "Meet McGraw." And he was getting nowhere fast, he decided, so he went to work in Europe, where they didn't typecast so much and he had some chance of playing a lead or getting the girl.

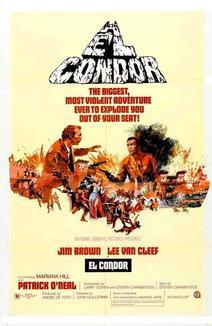

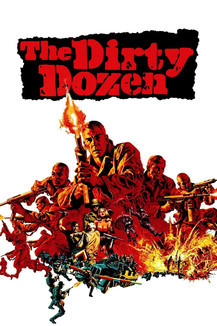

His first great European success was in "Farewell, Friends," opposite Alain Delon. That made him a lead, and then movies like "The Dirty Dozen" and "Rider on the Rain" made him a star. Although he worked for years in Europe, he refused to live there; he always maintained his home in America. He met Jill Ireland on a set in Germany in 1968, three years after her separation from David McCallum and a year after her divorce. And now, he says, "I don't have any friends, and I don't want any friends. My children are my friends." And in Europe, Asia and the Middle East, he is said to be the top box-office draw. "One of the ironies," he observed, "is that I made my breakthrough in movies shot in Europe that the Japanese thought were American movies and that the Americans thought were foreign."

That night in New York, the "Death Wish" company gathered to shoot a scene outside a grocery store on upper Broadway. Bronson said that, since he was here anyway, he would do some shopping. He began with a box of cookies. An old man, a New York crazy, was berating a box of Hershey bars because it wouldn't open. "What the hell's going on here? "he shouted at the box. Bronson opened it for him. The man hardly noticed.

While the location was being prepared, Michael Winner drank coffee across the street and talked about his enigmatic star.

"It's unnecessary for him to go into any big thing about what he does or how he does it," Winner said, "because he has this quality that the motion-picture camera seems to respond to. He has a great strength on the screen, even when he's standing still or in a completely passive role. There is a depth, a mystery - there is always the sense that something will happen.

I mentioned a scene in "The Stone Killer" in which Bronson has a gunman trapped behind a door. The gunman fires through the door, and Bronson, with astonishingly casual agility, leaps to the top of a table to get out of the line of fire.

"Yes," said Winner. "His body projects the impression that it's coiled up inside. That he's ready for action and capable of it. You know, Bronson is, as a human being, like that. That's not to say he goes about killing people. I'm sure that he doesn't"

A pause. "That's not to say he hasn't, in his day. Now he seems to have gotten a reputation for blowing up and hitting people on pictures. In my experience, he's not like that. He's a very controlled and reasonable person." Pause. "But there is a great fury lurking below."

The next afternoon, Bronson taped an interview for exhibitors with some people from the publicity department at Paramount. Bronson described the character he plays in "Death Wish:" "He's an average guy, an average New Yorker. In wartime, he would be a conscientious objector. His whole approach to life is gentle, and he has raised his daughter that way. Now he has second thoughts, and he becomes a killer."

Did you prepare for this character in any special way?

"No, because to play him I draw upon my own feelings. I do believe I could perform this way myself."

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {}; a2a_config.linkname = "Roger Ebert's Journal"; a2a_config.linkurl = "http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/"; a2a_config.num_services = 8;

Amazon.com Widgets

This story, found at last, has been long lost in the remote recesses of the Sun-Times archives. I wrote it for Midwest magazine, the paper's old Sunday supplement. For easier reading, there is a plain text version just below.

By Roger Ebert Holmby Hills, California

I. THE ACTUAL WILD GAME

The grounds, I was assured by a Playboy public relations man, make up a 5.1-acre compound. The site is surrounded by a brick fence, penetrated at two points by winding roads which are each three-quarters of a mile in length, one having to wind a bit more than the other to achieve that distance.

Inside the brick wall, he said, "is an actual forest, an actual wooded forest composed of giant redwood trees, and actual wild game roams in the actual park."

Wild game? I said. What kind of wild game?

"We don't know," he said.

You never do, do you? Wasn't it H. P. Lovecraft who suggested that one never knows, really, what lurks in the woods, gathering strength there in the dampness and dark, preparing for the day when it will spring out and gobble up children and little bunny rabbits? Yes.

I imagine maybe one of the first things Hugh Hefner will want to do, after he gets really settled in the Playboy Mansion West, will be to gather about him a hardy band of cronies and stage a safari through that 5.1-acre actual wooded area, identifying, where possible, the wild game that roams there. It will have to be a camera safari, of course, since one is not allowed to discharge firearms within Los Angeles County itself.

II. THE GREENING OF THE RAIN DRAINS

The mansion, I was told, has been appraised at $2 million including the grounds, the two greenhouses and the gardener's cottage. The furnishings are worth another $500,000. The place was designed in 1927 by an architect named Arthur Kelly, who specialized in mansions for the very rich. The difference between the very rich and you and me is that their mansions don't look like other people's mansions.

The mansion was occupied first by a man named Arthur Letts Jr., heir of a department store owner. It belonged most recently to Louis Statham, of the Statham Instruments. For the last 4 1/2 years, it has served as the unofficial hospitality residence of the City of Los Angeles, and the king and queen of Thailand have stayed there.

The mansion has 30 rooms and has been described as sort of Tudor Gothic or, according to Joyce Haber, a cross between Forest Lawn and "The Phantom of the Opera." But to be more specific, the Playboy public relations man painted a word-picture for me:

"It is a handcrafted fortress, with walls 18 inches thick made from reinforced concrete and stone. It has a slate roof, it has turrets, all kinds of turrets in the house, and archways, there's archways all over the place. Doors of golden oak, band-hewn. The rain drains have a kind of a little greenish tint to them because of the age, looking very, very rustic.

You enter the mansion through giant golden oak doors that swing right into the mansion's Great Hall, which is a very great hall. A shimmering crystal chandelier hangs overhead, and when you open the front door and walk in, you step right on an Italian marble floor. Windows extend from the floor to the ceiling... oak paneling is all around you... a Grand Staircase, the focal point of the Great Hall, consists of two separate sets of stairs that are curved from the main level right up to the upper level, forming a sloping, graceful arch, and, hanging right in the middle, there is a very many-tiered chandelier..."

III. WHAT TO DO ABOUT THE CATERPILLARS?

On the evening after the Academy Awards ceremony, I stepped through the band-hewn golden oak doors and paused for a moment on the Italian marble floor. My eyes lifted briefly to the many-tiered chandelier, and then rested on the Grand Staircase, where an assortment of Hefner's guests reclined on the stairs and watched the new arrivals.

This was Hefner's official housewarming for Playboy Mansion West, and there were two bands, two tents (one indoors, one outdoors) and a fire in the fireplace in every room. I walked through the Great Hall and found myself outside the mansion again, in the outdoor tent, where a band was playing and people were lined up three deep at the bar. Over in the distance, beyond the tent, giant orange Caterpillar earthmoving equipment was outlined against the night sky, with floodlights on them. I wandered back inside, and found myself in the living room, or one of the living rooms, talking to Jon Anderson, the columnist.

"Are you writing about this?" he said.

I guess so, I said.

"On deadline, or..."

No, I said, I'll be doing it for Midwest. Probably won't appear for a month or so.

"Good," said Jon. "Then I can show you something."

He led me across the room to the giant fireplace and pointed above it. There was a large reproduction of the "Mona Lisa" on the wall, done in needlepoint with a gold plaque underneath that said, "Barbi Benton - 1970."

Isn't that something, I said.

"We're going to use it in our column," Jon said. "It adds a nice, homey touch to the place, don't you think?"

Sure does, I said. Wilt Chamberlain's belt buckle passed by at eye level.

"It looks like one of those paint-by-number things, only in needlepoint," Jon said.

Wilt Chamberlain certainly is tall, I said.

"Needle-by-number," Jon said. "Or... point-by-point."

I wonder how long it took her, I said.

"It looks pretty complicated," Jon said. "The smile alone..."

Yes, I said, just the smile alone...

"Have you seen her?" Jon said.

Who?

"Barbi."

Not yet, I said. Just then Hugh Hefner himself walked into the room and nodded at everybody.

"Wonderful party, Hef," Jon said.

"Glad you're enjoying yourself," Hefner said. "We were worried right up to the last minute that we'd invited too many people. Then somebody came up with the inspiration of the outside tent, to handle the overflow. Now things are going great."

We nodded, and the three of us looked round the living room. Guests and bunnies and girls you vaguely recognized as former Playmates were all sitting around and, apparently, having great times. Big piles of floor-pillows were stacked here and there, but most everybody was sticking to chairs.

"The one problem with the outside tent," Hefner said, "was what to do about the bulldozers."

I was wondering about them, I said.

"We're digging a swimming pool back there," Hefner said. "Somebody said we should put potted trees in front of them, camouflage them somehow, but we finally decided, the hell with it, why not light them up as modem art or something. So that's what we did."

Somebody grabbed Hefner by the arm to introduce him to fresh guests, and Jon and I wondered back out onto the patio.

"Five centuries of art," Jon said.

What?

"From the 'Mona Lisa' to the Caterpillar."

Which one, I said, do you think will turn into a butterfly first?

"Hard to say," said Jon.

IV. TWO MALE LIONS

I left the tent and strolled alone through a portion of the 5.l-acre grounds. Stone walks surrounded the house, and from the front you could hear the excitement of new arrivals, pouring out of their limousines and Yellow Cabs and hurrying through the giant golden oak doors.

My steps led me some distance from the house, and the sound of the rock band came drifting to me...

Rap... rap... rap... they call him the rapper...

Something caused me to think about a character I hadn't thought of in some time, the Great Gatsby. There's a scene in that novel by Fitzgerald telling of the almost nightly arrival of fresh carloads of guests, all eager to share Jay Gatsby's fabulous hospitality, and to glory in his famous home. Later on in the novel, Gatsby's hospitality comes to a sudden end, but not all the guests get the word, and for several weekends thereafter, cars continue to come out from the city and pull into the silent driveway, and then leave when they see there's no party.

At any given moment in history, I decided, there is a man whose job it is to give famous parties. Sometimes he is a fictional person, sometimes he is real. Sometimes he is the Great Gatsby, sometimes William Randolph Hearst, or Hugh Hefner...

Coming back toward the house, I found myself suddenly in the presence of two stone lions. They flanked a short flight of steps and gazed back toward Los Angeles. They both had manes, which meant they were both males. I decided their names were Bill and Hugh, Bill on the right looking over somewhat curiously at his neighbor.

V. TWO MORE MALE LIONS

Back inside the tent, Ryan O'Neal was leaning against the bar with a drink in his hand and looking out over the tables to the dance floor at the other end of the tent. There was something in his look that seemed peculiar until I got it figured out. Then it seemed understandable enough. Ryan O'Neal wasn't looking out over the crowd. He was in the act of being Ryan O'Neal looking out over the crowd. Does that make any sense? What I mean is, he wasn't really looking; he was aware of himself as Ryan O'Neal, being seen to be looking.

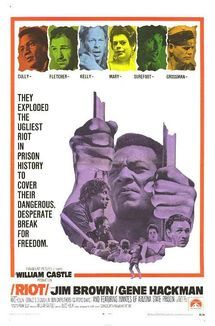

That doesn't say it either, but the hell with it. The fourth lion was Jim Brown, who moved through the crowd with a kind of dangerous grace, attracting a great deal of attention even though he was apparently doing nothing to inspire it. People, were wondering, I suppose, whether he had really thrown that girl off the balcony, etc.

Some people occupy space differently than others. Jim Brown encloses space while Ryan O'Neal merely fills it.

VI. TWICE AS BIG AS ILLINOIS

There were girls everywhere, but they seemed to be filling space like Ryan O'Neal and not like Jim Brown. It occurred to me that a lot of the girls you see at parties like this lack some dimension, the third or the fourth, maybe. They are pretty and they smile, but they're girls, not women.

Why? Because they lack the final measure of self-confidence to be women, I think. The Playboy girl is a commodity, to some degree; she is an image to be packaged and merchandised, as much of a symbol as a Chevrolet or a Baggie. Her success depends upon your acceptance of her. If you like her, if she "turns you on," then she has succeeded. But if she doesn't, then she's failed as everything: Girl, symbol, commodity.

A girl who is uncertain at her core can never be really interesting, no matter how beautiful she may appear to be on the surface. She isn't really there, and that fact frightens her. There were some real women there. Polly Bergen and Edy Williams (two names you might not have expected to come across on the same list) had that dimension. You felt they were people, and knew they were people. But a lot of the Bunnies seemed oddly transparent.

Some people have the notion that a Hefner party is sexy and sensuous and the next thing to a genteel sort of orgy. Hefner's parties are fun, but in an entirely different way than the image would suggest. The food is good, the booze is free and keeps coming, and there are sure to be interesting people there. It's just that, somehow, all these people who look like such good friends when Playboy runs a layout about a Hefner party aren't good friends - have probably just met tonight - and are having a conventionally good time. We've all read about that little room behind the waterfall in Hef's Chicago swimming pool, but what good is the little room when people inside it are clearly visible? A Hefner party is like that little room: You swim beneath the waterfall, but, inside, the lights stay on.

And so, finally, the conversation gets around to Hefner himself (the conversational obsession at most of his own parties), and you wonder whether this turns him on, and how much he enjoys it. My private notion is that he enjoys it a lot; who wouldn't? If I had his fortune, I'd throw parties all the time for my friends. Wouldn't you? I think throwing the parties would be more fun than attending them.

Perhaps that's at the core of Playboy Mansion West: Now there can be great parties in California, just as there have been for years in Chicago, and all of this year's Hollywood people can come and mingle and talk, be photographed by the omnipresent Playboy photographers, eat expensive beef, watch the shrimp cocktail bowl being constantly replenished, name their brand of Scotch, wonder who everybody else is (and who they are) and try not to think about the stone lions.

Wondering down the Grand Staircase, I passed two guests who were talking about the Mansion West.

"How does this place stack up with his other place?" the first guest said.

"This one is twice as big as Illinois" said the second.

"It must be great to have two places," said the first.

"Better than only having one," the second said.

VII. INTRODUCTION IN THE FORM OF A SEQUEL

All these things and thoughts occurred the night after the Academy Awards. On the night before the Academy Awards, there was a big party at Le Bistro, the famous Beverly Hills club.

Hefner came with Barbi on his arm and seemed to be having a great time. Edward G. Robinson, who was also there, offered Hefner some pipe tobacco that, Robinson said, acted as an aphrodisiac. Hefner and Robinson shared a good laugh over that, and then Hefner moved easily through the room, talking to people. The party was crowded and noisy, and there was a band and lots of good things to eat and drink. But by 11 o'clock or so the people started to drift away (they don't stay up late in Hollywood; they're home by midnight, usually).

Hefner and Barbi left, and then there were maybe only 20 people remaining; the hard core who had negotiated special arrangements with the waiters to bring the booze to the table in bottles, not glasses, to save time. This group talked for 45 minutes or so while the waiters stood by and waited patiently for the party to finally be over. And then Hefner and Barbi came back into the room.

Didn't you already leave? somebody said.

"We took off, but then we thought we'd come back and see if there was still anything happening," Hefner said.

In reading "The Great Gatsby," I've sometimes had the notion that one of those great limousines that came out from the city, and paused in Gatsby's quiet driveway before driving away, was driven by Gatsby himself.

More than 150 of my other special pages are linked in the right column. var a2a_config = a2a_config || {}; a2a_config.linkname = "Roger Ebert's Journal"; a2a_config.linkurl = "http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/"; a2a_config.num_services = 8;

FFFgoer Andra Takacs files her account of the 2006 Floating Film Festival:

LOS ANGELES -- I walked in to talk to Pam Grier with these words of Quentin Tarantino fresh in my mind: